Responding to Environmental Catastrophes:

An Evolving History of NOAA's Involvement in Oil Spill Response

No matter the size or location, oil spills can have drastic impacts on human and environmental health. In over 30 years of responding to oil spills, NOAA has provided scientific support for over 2,000 marine and inland oil and chemical spills. Working with the U.S. Coast Guard and state and local governments, NOAA scientists continue to minimize impacts and restore effected ecosystems to pre-spill conditions.

- Introduction

- Disaster on Alaska's North Slope

- Product Advancements

- Spill Respnse Today

- Looking Forward

The Argo Merchant spilling its No. 6 heavy fuel oil into rough, 10-foot seas, 29 miles southeast of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. Click image for larger view.

On December 15, 1976, the tanker Argo Merchant ran aground on the Nantucket Shoals and eventually broke in half several days later. The entire 7.7 million gallons of heavy fuel oil carried by the Argo Merchant spilled into the Shoals, threatening damage to the famous Massachusetts fishing grounds. Over the days and weeks that followed, NOAA began its first major coordinated oil spill response activity.

As a result of the Argo Merchant disaster, NOAA put additional resources towards spill response. The NOAA Hazardous Material Response Division (HAZMAT team) was created to provide scientific expertise during a response incident. Scientific Support Coordinators (SSCs) were strategically located around the country to coordinate scientific information. Furthermore, standard methods for assessing oil spilled on the sea were established and a series of trajectory and fate modeling programs were created to provide the Coast Guard with forward vision when responding to a spill.

The HAZMAT team (now the Emergency Response Division) has grown from a handful of oceanographers, mathematicians, and computer modelers into a highly diverse team of chemists, biologists, geologists, information management specialists, and technical and administrative support staff. This article details changes in NOAA spill response and support over the last 20 years.

Disaster on Alaska's North Slope

One of the most widely publicized spills in recent history was undoubtedly the March 24, 1989 Alaska North Slope Exxon Valdez oil spill, which released 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska's pristine Prince William Sound.

A shoreline cleanup crew attempting to use high-pressure, hot water-washing to clean an oiled shoreline at the site of the Exxon Valdez spill. Click image for larger view and complete caption.

NOAA's HAZMAT team arrived at the scene of the spill within 24 hours. HAZMAT scientists supported the massive cleanup and damage assessment conducted by the Coast Guard, the State of Alaska, and the responsible parties by providing forecasts, guiding aerial observers, making recommendations on cleanup actions, and monitoring the recovery of oiled shores.

While the Exxon Valdez oil spill was a terrible disaster, the cleanup effort provided emergency responders with a testing ground for both old and new spill response methods. Bioremediation, the use of living organisms such as bacteria to clean up oil spills, was a popular practice at the time and there was great pressure to apply this technique to oiled shores. However, NOAA Emergency Responders and colleagues at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) quickly learned that marine environments are often replete with oil-degrading bacteria. Simply removing bulk oil and providing exposure to air maximizes the rate of oil degradation with little need for the additional chemical products that were being used in bioremediation projects at the time. Responders also learned that pressure-washing graveled beaches increased injury to intertidal resources and may have even contributed to lingering oil deposits. But perhaps the greatest lessons came from enhanced information exchange, extensive training, and management that were precipitated by the spill response.

The Exxon Valdez spill prompted Congress to enact the Oil Pollution Act (OPA) of 1990, which gave NOAA and the EPA greater ability to respond to spills and created a trust fund financed by the oil tax to aid in cleanup operations. The OPA also led to improved contingency planning in the event of future oil spills and rapid notification of incipient incidents, which have gone a long way to reduce oil releases and impacts of spills on marine resources. In general, both the number and volume of oil spills has fortunately decreased since the OPA was passed.

Technology, Process, and Product Advancements

Over the years, NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R) has developed numerous electronic products and Emergency Response Job Aids (field guides and manuals for on-scene response coordinators).

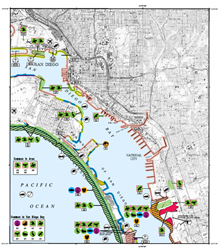

Sensitive environment mapping must be an integral component of overall spill planning. Sensitivity maps are not an end in themselves; rather, they are a starting point for prevention, planning, and response actions. The resource definitions in NOAA’s sensitivity maps provide guidance for local organizations developing spill plans. Above is an ESI map of San Diego Bay and vicinity. Click image for larger view.

Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) maps, first completed in 1979 after the Ixtoc 1 exploratory oil well blew out, provide information about coastal shoreline sensitivity and both biological and human-use resources. These maps greatly aid responders by identifying resources at risk before and during an oil spill, to establish cleanup methods and priorities.

Another critical tool in chemical spill response is the Computer-Aided Management of Emergency Operations (CAMEO) suites, which NOAA partnered with the EPA to develop in 1986, partially in response to the catastrophic 1984 Bhopal Union Carbide chemical release in India that killed thousands of people. CAMEO provides a quick answer in terms of what risks may be caused by a chemical release. Today, CAMEO includes a chemical database and a Chemical Reactivity Worksheet to predict hazardous chemical reactions.

Using scientific models and oceanographic expertise, OR&R has successfully directed the Coast Guard to "mystery" incidents and spills, including leaking wrecked vessels submerged many decades ago. For instance, NOAA helped identify and locate the USS Chehalis tanker that sunk in 1949 from a fire on board and is believed to have been the source of the "mystery" spills in Pago Pago Harbor, American Samoa. OR&R is also currently working on ways to forecast and hunt down submerged oil, an important challenge as industry is increasingly transporting heavier fuels.

Spill Response Today - Training and Preparation

U.S. Coast Guard responding to the Selendang Ayu oil spill in the Aleutian Islands. Click image for larger view.

The typical spill today involves a scenario such as a fishing boat sinking and releasing 2,000 gallons of diesel fuel. While these spills are not large in nature, catastrophic incidents do still occur. The M/T Athos I, on November 26, 2004, spilled about 265,000 gallons of crude oil into the Delaware River near Philadelphia. The M/V Selendang Ayu freighter in the Aleutian Islands lost power and ran aground off Unalaska Island on December 8, 2004, releasing more than 400,000 gallons of bunker oil into the marine environment. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were the cause of dozens of oil spills, further devastating the Gulf Coast.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, a responder attempts to contain recently spilled oil with a boom in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA focused emergency response efforts on 16 significant pollution incidents and conducted overflights to identify and document oil spills along the Gulf Coast. Click image for larger view.

Fortunately, NOAA scientists, technicians, and response personnel are continually training new federal, state, and industry responders in the science of spills and spill response, observation, and assessment techniques; risk assessment and planning; and information management. Thousands of people have benefited from such training, and in 2004 alone, over 800 individuals were trained by OR&R scientists in emergency response methods.

At NOAA's Safe Seas Events, the Emergency Response Division (ERD) has provided critical training to several hundred NOAA resource trustees, including National Marine Sanctuaries and NOAA Fisheries. ERD highlighted response preparedness and capabilities to deliver data, observations, forecasts, and expertise towards the goal of protecting life, commerce, and the environment during a spill emergency. This vital training must continue into the foreseeable future to further reduce injury to our marine and coastal environment.

The command post at a national Spill Of National Significance, or “SONS,” Drill in Long Beach, California, during the Spring of 2004. During events such as these, NOAA works with state, federal, and responsible parties to learn how best to respond in the event of a spill. Click image for larger view.

NOAA is continually learning, adapting, and collaborating from each spill experience. Recently, NOAA scientists learned how to incorporate real-time data on weather and ocean currents into trajectory models. These data will increasingly be provided by the nation's Integrated Ocean Observing System, which will greatly increase speed and accuracy in forecasting the movement of oil and other hazardous materials.

NOAA's spill response tools also have many other applications in the ocean community. For example, OR&R models have been used and are currently being adapted to forecast the dispersal of larvae of threatened species and the movement of noxious marine organisms in the marine environment.

Looking Forward

This photo was taken from a NOAA overflight of Athos I oil spill cleanup on December 2, 2004, less than a week after the spill. At this spill, NOAA scientists provided hazard shoreline assessments, information on oil behavior and movement, cleanup recommendations, risk communication, and public outreach.

Public awareness of the damaging effects of oil in the marine environment has increased dramatically over the last 20 years. NOAA, along with its federal partners, must use its extensive experience as well as the tools and products provided to emergency responders to continue leading the way in efficient and effective oil spill response. NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration will continue to grow and adapt to the changing environment and support the NOAA mission of conserving and managing our nation's coastal and marine resources.

Contributed by Dr. Alan Mearns and Mary Teresa Swift, NOAA's National Ocean Service