Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Meteorological Observers in the American West

Scientific observations were a prominent, though lesser-known, aspect of the expedition of discovery led by Lewis and Clark in 1804-1806. The explorers chronicled flora and fauna, weather observations, and astonishingly precise measurements of temperature (until the rigors of the journey claimed their last remaining thermometer). A review of the historical records and journals of the era by two NOAA scientists revealed that meteorological data and personal weather-related observations collected by these pioneering weather observers are worthy of celebration.

- Introduction

- About the Expedition

- Weather Observations

- Contributions that Span Centuries

- Works Consulted

In May 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark began an expedition of discovery that would become one of the epic sagas in American history. The captains and the men of the Corps of Discovery sailed three boats up the Missouri River out of the frontier town of St. Louis, Missouri, with more than 3,500 pounds of materials and supplies, in search for a way over land to the Pacific Ocean.

The expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark was initiated by Thomas Jefferson in 1803 to explore and map America. Click image for larger view.

They were a military expedition, assembled by commander-in-chief and President Thomas Jefferson, and they were well armed for exploration in locations where neither Americans nor Europeans had ever traveled. They carried the best Kentucky rifles, powder horns, and more than 400 pounds of lead for shot. Their supplies also included portable soup, fish hooks, mosquito netting, flints, the finest instruments of navigation, a microscope, and an array of goods such as colored beads and cloth to trade and give to Native Americans.

Although the drama of their adventures achieved legendary proportions, it is less well known that they made numerous contributions to diverse areas of science.

Susan Solomon and John Daniel, a pair of NOAA scientists with the Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, reviewed the historical records and journals of the era. Solomon and Daniel discovered that meteorology can be added to the list of pioneering achievements associated with the 1804-1806 expedition of Lewis and Clark.

About the Expedition

These bronze statues, located in Fort Atkinson, Nebraska, depict Lewis and Clark's first meeting with Native Americans during their journey. Click image for larger view.

Thomas Jefferson had hopes of sending an expedition westward across America as early as 1783, but it was not until several years later that his dream became a reality. Jefferson's letter of instruction to Lewis in 1803 stated that the primary "object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & . . . whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado, or any other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce."

But Jefferson's intentions extended beyond politics into several areas of science, including climate science. His instructions to Lewis called for a range of observations of potential value not just for economic gain, but also for knowledge of the soil, plants, animals, and minerals that were encountered. Jefferson also instructed Lewis to make observations of "climate, as characterized by the thermometer, by the proportion of rainy, cloudy, and clear days, by lightning, hail, snow, ice, by the access & recess of frost, by the winds prevailing at different seasons..."

The Weather Observations of Lewis and Clark

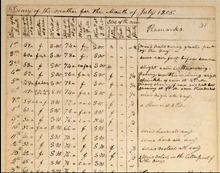

While the primary goal of the mission of Lewis and Clark was economic and strategic, they also diligently and successfully recorded weather observations throughout their journey. Weather data exist in the handwriting of both Lewis and Clark. So concerned with safeguarding their irreplaceable record, the two captains recopied each other's records verbatim. From September 19, 1804 until September 6, 1805, when the last thermometer was broken crossing the Bitterroot Mountain range near the Montana-Idaho border, temperatures were measured each day at sunrise and at 4 p.m.

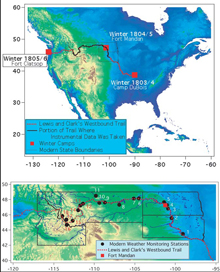

These maps illustrate the Lewis and Clark westbound trail. Click image for larger view and full caption.

Solomon and Daniel reviewed Lewis and Clark's pioneering daily sunrise measurements on the North American High Plains. In addition to recording temperature data, Lewis and Clark and their men also documented typical spring and fall Western snows, flash floods, and warm Oregon winters—features of the climate that often surprised and occasionally plagued these men from the eastern seaboard. At one point, Clark wrote of being so wet and cold that he was "fearful [his] feet would freeze in the thin moccasins which [he] wore."

Despite the often extreme conditions, Lewis meticulously calibrated the thermometers, writing of "testing [a thermometer] with water and snow mixed for freezing point, and boiling water for the point marked boiling water." Such calibrations ensured that the records taken by Lewis and Clark were consistent and accurate. And indeed, when Solomon and Daniel compared the records of Lewis and Clark with many decades of collection of modern data at U.S. Cooperative Observer Network stations along the route of Lewis and Clark, they found that the seasonal evolution and variability of temperatures recorded by Lewis and Clark over 200 years ago agree very well with the modern record. For example, Lewis and Clark experienced average minimum temperatures for June/July in Montana of about 50° F (10° C). This average is within 2° F of expectations from modern data.

The NOAA analysis thus shows that Lewis and Clark carried out their weather observations, as directed by Jefferson, with skill, tenacity, and considerable success. Solomon and Daniel credit much to Lewis' careful attention to the calibration of the thermometers. Solomon noted that a "comparison of their data to modern measurements reveals that [Lewis] and Clark clearly nailed [the weather observation] challenge, just as they did so many others on the pioneering journey."

Contributions that Span Centuries

In addition to their countless other discoveries across many fields of science, the analysis by Solomon and Daniel illustrated that Lewis and Clark's observations of temperature over a year on the High Plains were of high quality, which was certainly due in large part to careful attention to procedure.

Without the calibrations performed by Lewis, the data surely would have been worthless, but comparison of their observation with the modern record now attests to the success of that work. Although the nature of their lives, their diets, the wildlife, and many of their interactions with people were dramatically different from their home states and from those of the modern West, their observations of western American climate are familiar.

Products related to the intellectual efforts of Lewis and Clark include this weather record for July 1805 near the area of Great Falls, Montana. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The climate they documented so accurately for the first time can best be described as "normal," but their powers of observation were certainly noteworthy. While the single year of meteorological data recorded by the Corps of Discovery is not sufficient to enlighten the science of meteorology in a substantial way, the accuracy of the findings reveals yet another area in which Lewis and Clark certainly did succeed not only as explorers but also as scientists.

As NOAA celebrates 200 years of science, service, and stewardship, we can look back to the remarkable contributions of Lewis and Clark in many areas of discovery. In meteorology, as in other subjects, the passage of centuries has only shown more ways in which their expedition was a triumph of its era.

Article adapted from: Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Meteorological Observers in the American West