Evolving Strategies to Protect Marine Sanctuaries

The NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Program manages a national network of ocean and Great Lakes areas designed to protect natural and cultural resources, while allowing people to use and enjoy our oceans and coasts. The first sanctuary was created in 1975 and the network has since grown to include 13 national marine sanctuaries and one marine national monument.

- Introduction

- Resource Protection

- Science and Exploration

- Education and Outreach

- New Management Strategies

- Focus on Cultural Resources

- Conclusion

- Works Consulted

From its inception in 1972 through the early 1990s, the NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Program established 11 sanctuaries, ranging in size from less than one square mile to more than 5,000 square miles. However, during the same period, the program’s budget increased only modestly. In the mid-1990s, the public and elected officials began to recognize the value of marine sanctuaries, and acknowledged that the sanctuary program would require greater financial support if it was to fully realize its educational, scientific, and resource protection goals.

This map shows the National Marine Sanctuary System, including 13 marine sanctuaries and one marine national monument. Click image for larger view.

Today, the sanctuary program manages 13 national marine sanctuaries and one marine national monument. Over the last decade, the sanctuary program’s budget and responsibilities have increased to better manage and protect sanctuary resources. With the increased expectations of the public, the sanctuary program has employed innovative approaches to marine management and expanded its science, education, and resource protection programs.

Resource Protection

The National Marine Sanctuaries Act calls for the sanctuary program to protect the natural environment within sanctuaries, while facilitating compatible commercial and recreational uses. Over time, the sanctuary program has encountered a variety of challenges to its resource protection efforts. The program’s management strategies have evolved accordingly, enabling it to fulfill its mandate by developing a wide range of solutions to challenges.

Queen angelfish are a favorite of the many divers and snorkelers who visit the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary each year. Click image for larger view.

Strategies like marine zoning and the creation of “no-take” or “limited-take” reserves, such as those established in some areas of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), are being used in an effort to maximize sanctuaries’ ability to protect important resources, while still allowing for compatible commercial and recreational activities.

Initial research results indicate that this system of reserves is paying off. Scientists have documented increases in the size and numbers of spiny lobster in the Western Sambo Ecological Reserve, which is part of a larger network of 24 “no-take” zones within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. These results make a strong case for the use of this innovative management tool.

Science and Exploration

Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary is an important summer feeding ground for humpback whales. Click image for larger view.

Science and exploration are important parts of the sanctuary program’s mission because they contribute to a better understanding of the world’s oceans and can yield valuable information that improves the program’s ability to manage sanctuaries effectively.

Over the last decade, research and monitoring efforts by the National Marine Sanctuary Program have moved from early site-specific projects to a strategic system-wide research and monitoring program. This program includes efforts like deepwater monitoring of marine reserves in the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. It also includes research using non-invasive tags on baleen whales in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. Based on data gathered from the tags, the sanctuary program has recommended shifting vessel traffic lanes north by 12 degrees to drastically reduce whale-ship collisions.

The sanctuary program has expanded its research capabilities by investing in small vessels that are designed specifically to meet sanctuary science needs. In the past year, three catamaran vessels similar to the R/V Shearwater have been commissioned for use at Stellwagen Bank, Florida Keys, Monterey Bay, Gulf of the Farallones, and Cordell Bank national marine sanctuaries, greatly expanding researchers’ access to those areas.

Education and Outreach

Over the last 30 years, the sanctuary program has increasingly emphasized the importance of education and outreach to help the public understand the importance of protecting the world’s oceans. A major recent development in the sanctuary program’s education and outreach efforts is the ability to bring the ocean environment to landlocked Americans using “telepresence” technology.

As well as providing a wonderful setting for research and recreation, the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (CINMS) is a wonderful classroom. Los Marineros is a marine education program for children founded by the CINMS in 1987 and administered by the Santa Barbara Natural History Museum. Click image for larger view and credit.

Telepresence technology allows the sanctuary program to transmit real-time, interactive underwater exploration to homes and classrooms around America through a new Web site called OceansLive. This Web portal connects people to sanctuary natural and cultural resources by allowing them to view real-time footage from underwater cameras on research cruises. The portal makes the wonders of the ocean more widely accessible than ever before.

With the sanctuary program’s telepresence effort, the organization will be able to reach out and connect all 300 million Americans to the importance of the ocean in their everyday lives. This is a giant step forward from the comparatively limited reach allowed just 10 years ago.

New Management Strategies

Congress has reauthorized and amended the Sanctuaries Act several times since it was created in 1972. In 1996, one such amendment allowed for the creation of sanctuary advisory councils, which are groups of community members and stakeholders that provide management recommendations to sanctuary superintendents. By 2005, every sanctuary had established a sanctuary council — a major step forward in creating lines of communication between the sanctuary program and local constituents. This step improved sanctuary directors’ abilities to make positive, well-informed management decisions.

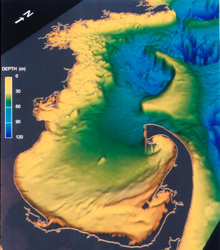

Stellwagen Bank sits like a wall at the edge of Massachusetts Bay, forcing water from the Gulf of Maine and waters inside the Bay around its edges and over its surface. The sanctuary's seafloor consists of a variety of habitat types found across the Gulf of Maine. Click image for larger view and credit.

Another recent congressional amendment required that each sanctuary management plan — a document serving as a blueprint for guiding sanctuary science, education, and resource protection activities — be revised every five years. Prior to this amendment, there was no requirement that plans be updated. The new management plans are drafted with extensive input from local stakeholders and will allow sanctuary superintendents to evaluate the effectiveness of existing programs and identify new threats to the health of the sanctuaries. With the revised management plans, the sanctuary program will be able to improve current and future resource protection, science, and education programs.

Increased Focus on Cultural Resources

View of the wreckage of the USS Monitor. The structure to the right marks the original location of the turret, which was recovered in August, 2002.

Although the first sanctuary, USS Monitor, was established to protect a significant historical resource—a Civil War shipwreck—it was not until 2000 that another sanctuary, Thunder Bay, was designated specifically for its historical resources. As Thunder Bay was being established, the sanctuary program recognized the need to commit greater resources to the preservation and understanding of significant historic and cultural resources.

The genesis of this thinking resulted in the formation of a Maritime Heritage Program that would help focus additional research and education about the extensive historical and cultural resources within the entire National Marine Sanctuary System.

Conclusion

The sanctuary program has evolved since its creation in 1972 and has developed a variety of approaches to fulfill its mandate and ensure its impact is long lasting. Today, the sanctuary program plays a critical role in the nation’s marine conservation efforts. The sanctuary program’s 13 national marine sanctuaries and one marine national monument protect an area greater in size than all 385 U.S. national parks combined.

The Hawaiian monk seal, one of the rarest marine mammals in the world, is one of many species that is found only in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Click image for larger view.

The program has also demonstrated that, in addition to resource protection, sanctuaries provide opportunities for research, education, and exploration of America’s natural and cultural heritage. Through these avenues, national marine sanctuaries are accessible and relevant to the general public. The sanctuary program is working harder than ever to protect, understand, and share our oceans’ treasures with all 300 million Americans and the entire world.

Works Consulted

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2006). National Marine Sanctuary Program: State of the Sanctuary Report 2005-2006. Retrieved November 3, 2006, from: http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/sos05/sosreport2005.pdf.