Building a Network of Estuaries

The Coastal Zone Management Act, administered by NOAA, provides for management of the nation's coastal resources including the Great Lakes, and balances economic development with environmental conservation. Among other things, the Act established the National Estuarine Research Reserve System, a network of 27 estuarine locations in 22 states and Puerto Rico, representing different biogeographic regions of the United States that are protected for long-term research, water-quality monitoring, education, and coastal stewardship.

- Introduction

- Beginnings: Growing Concern

- CZMA and the Reserves

- Early Years: 1970s

- Growth and Expansion: 1980s

- Research, Education, and Outreach

- Conclusion

- Works Consulted

Estuaries are key junctions in the great planetary hydrologic (water) cycle. They are the zones on continental coasts where fresh river water streaming from mountains and plains reaches sea level and mingles with the salty ocean tides.

Coastal wetlands are crucial nursery habitats for many species of marine animals, including commercially valuable fish and shellfish. Healthy wetlands, like Mission Copano Bay at Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve in Texas, also help buffer the impact of coastal storms and minimize damage to human communities. Click image for larger view.

Estuaries are more than just a mixing point for fresh and salt water. Estuaries are rich and complex ecosystems that form the foundation for much of ocean life. Their grass beds are nurseries for many of the fish and shellfish that are important to sport and commercial fishing. Shorebirds and raptors depend on the crabs and fish that live in the mud and the meandering marsh creeks. Vegetation filters sediments and receives nutrients from water flowing in from upstream. Estuaries also moderate the impacts of large storms, protecting human and natural upland communities from excessive damage.

Recognizing the importance of these estuarine areas, Congress mandated the development of a network of estuaries to serve as living and learning laboratories as part of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. This article traces the history of the establishment of this network - the National Estuarine Research Reserves System (NERRS).

Beginnings: Growing Concern

For most of America's history, our extensive shoreline was viewed as part of the vast national bounty - important as a source of abundant seafood and recreation. In the economic boom that followed World War II, the growing population spent more of its leisure time near the coast. This led to increased development of housing, roads, shopping centers, and boating facilities close to the shore.

By the 1960s, scientists had grown concerned about the effects of all these activities on coastal and estuarine ecosystems and the ability of these ecosystems to sustain the oceans and growing human communities.

The CZMA and a System of Reserves

In 1972, policy makers listened to the concerns and recognized the need to pass the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA). This legislation spelled out the problems facing the coasts in great detail: "Increasing and competing demands...have resulted in the loss of living marine resources, wildlife, nutrient-rich areas, permanent and adverse changes to ecological systems, decreasing open space for public use, and shoreline erosion.... Important ecological, cultural, historic, and esthetic values in the coastal zone, which are essential to the well-being of all citizens, are being irretrievably damaged or lost."

Among the provisions of the 1972 law was the establishment of a national system of estuarine sanctuaries protected for purposes of long-term research, public awareness, and education. This system was the predecessor of today's National Estuarine Research Reserve System.

Management of reserves, like the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Rhode Island, is a partnership between NOAA and the coastal states. Click image for larger view.

The key to effective protection of coastal and ocean resources was to encourage the states to exercise their full authority over the lands and waters in the coastal zone. Accordingly, the estuarine sanctuary system was based on a strong state-federal partnership that empowered the states to manage their own coastal issues with federal financial support and guidance. A state agency or a university manages each of the sanctuaries (now reserves); NOAA contributes 70 percent of the funds for these sanctuaries and the state funds the remaining 30 percent.

The Early Years: The 1970s

During the estuarine sanctuary system's early years, NOAA and its state partners strove to fulfill the provisions of CZMA and establish ground rules for the system in the years ahead. Designation of new reserves proceeded deliberately and carefully. In accordance with the law, states had to nominate potential estuarine sanctuary sites. NOAA evaluated the nominations to ensure that state laws were strong enough to provide long-term protection and to meet other requirements for research, education, and public outreach.

During the 1970s, NOAA designated five estuarine sanctuaries: South Slough, 4,400 acres in Coos Bay, Oregon (1974); Sapelo Island, 6,110 acres on the Georgia coast (1976); Rookery Bay, 110,000 acres in southwest Florida (1978); Apalachicola Bay, 246,000 acres on Florida's panhandle (1979); and Elkhorn Slough, 1,400 acres in Monterey Bay, California (1979). Click image for larger view.

During the 1970s, NOAA designated five estuarine sanctuaries. South Slough, a 4,400-acre arm of Coos Bay in southern Oregon, was the first sanctuary designated in 1974. Other designations included the first reserve with mangrove forests (Rookery Bay, Florida), one of the largest components of the system (Apalachicola Bay, Florida), and the first protected estuary in California (Elkhorn Slough).

Growth and Expansion: The 1980s

By 1980, the estuarine sanctuary system encompassed more than 360,000 acres on the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf Coasts. Those first five sanctuaries also fulfilled one of the key provisions of the CZMA: regional diversity, representing the Columbian, Carolinian, West Indian, Louisianian, and Californian biogeographical regions, respectively.

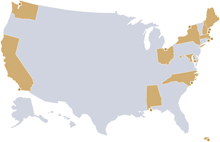

This map identifies 29 biogeographic regions in the U.S. As the map shows, reserves are found in the majority of these regions. Click image for larger view.

The 1980s brought expansion and a name change as a dozen new protected areas joined the system. In 1986, the CZMA was amended, and the existing sanctuaries all became national estuarine research reserves, part of the NERRS.

Over the course of the decade, a dozen new reserves came into the system. The total acreage added was less than 58,000, but the scope and diversity of the system continued to grow, adding three new biogeographic regions: Virginian, Great Lakes, and Acadian.

Reserves added to the system in the 1980s included: Padilla Bay, Washington (1980); Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island (1980); Old Woman Creek, Ohio (1980); Jobos Bay, Puerto Rico (1981); Tijuana River, California (1982); Hudson River, New York (1982); three reserves in North Carolina (1985); Wells, Maine (1986); two reserves in the Chesapeake Bay, Maryland (1985); Weeks Bay, Alabama (1986); Waquoit Bay, Massachusetts (1988); Great Bay, New Hampshire (1989). Click image for larger view.

The 1980s were full of "firsts" for the NERRS network. Jobos Bay in Puerto Rico, the first reserve with a coral reef, was added to the system. Tijuana River in California joined the system and brought with it new implications for international ecosystem management. The Hudson River in New York became the first multi-site reserve and Wells in Maine became the first reserve to be managed by a private rather than state agency (Laudholm Trust).

As the 1980s came to a close, the foundation was laid for establishment of long-term research, education, and outreach programs as the original law had envisioned. The system now consisted of 17 reserves in all but one of the major biogeographic regions. This one missing region, fjords, is now represented by the Kachamak Bay reserve in Alaska, added in 1999.

A Focus on Research, Education, and Outreach

During the 1990s, the following reserves were added to the system: four sites on the James River, Virginia (1991); North Inlet-Winyah Bay and ACE Basin, South Carolina (1992); two sites in Delaware (1993); Jacques Cousteau Reserve, New Jersey (1998); Kachemak Bay, Alaska (1999); Grand Bay, Mississippi (1999); and Guana Tolomato Matanzas, Florida (1999). Click image for larger view.

By the mid-1990s, with 21 designated reserves and a wide representation of biogeographic regions, NERRS began developing national programs to coordinate the research, education, and stewardship activities at the reserves. Existing and new reserves could now receive funding to participate in the System-Wide Monitoring Program, the Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and the Coastal Training Program. Also, reserves could mutually benefit from each others' experiences and expertise.

The new century has brought in two more reserves: California's San Francisco Bay in 2003 and Texas's Mission-Aransas in 2006, bringing the system to its current total of 27 reserves.

Conclusion

As a voluntary federal-state partnership, CZMA is designed to encourage state-tailored coastal management programs. NERRS is a network of protected areas established for long-term research, education, and stewardship. This partnership program between NOAA and the coastal states now protects more than one million acres of estuarine land and water, which provides essential habitat for wildlife.