"The Plotter" — Mr. Lloyd "Shorty" Gilden

NOAA's Office of Coast Survey conducts hydrographic surveys to measure the depth and bottom configuration of water bodies, to produce the nation's nautical charts and ensure safe navigation of U.S. waters. The surveys also identify sea-floor materials, dredging areas, cables, pipelines, wrecks and obstructions, and fish habitats. They support a variety of activities such as port and harbor maintenance, coastal engineering, coastal zone management, and offshore resource development.

- Introduction

- Lloyd "Shorty" Gilden

- Just For Fun…

- At Work on the Water…

- The Plotter in Action

- Remembering Shorty

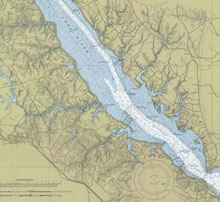

A nautical chart is a graphic portrayal of the marine environment. Unlike some other types of maps, it has a very serious use as a tool for mariners to navigate safely at sea. Click image for larger view.

Hydrography is the science which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of bodies of water and surrounding land areas, with a special emphasis on information pertinent to navigation. NOAA and its predecessor agencies have been collecting hydrographic data for nearly 200 years. Over this time period, how hydrographers collect and represent time, position, and depth information has changed.

What follows is a first-hand recollection from Navigation Response Team 2, NOAA hydrographer David B. Elliott of his mentor and friend, cartographer and plotter extraordinaire—Lloyd Gilden.

Lloyd "Shorty" Gilden

Shorty (right) celebrates his retirement from the Coast Survey in 1979. Click image for larger view.

When I met him, he had a sinister sneer in his laughter, the kind of laugh that makes you realize you are dealing with a unique personality. And indeed, “unique” would be the word to describe him. The year was 1977, and I had just reported to work with a “Hydrographic Field Party.” I was met by Lieutenant Stan Iwamoto, the NOAA Corps Officer in Charge; Robert Snow, the Launch Engineer; and the man with the laugh—Lloyd “Shorty” Gilden, the Cartographer.

I call Shorty “The Plotter” because plotting hydrographic data was his foremost and primary function. He was really much more than that – kind of a walking hydrographic text book. Shorty spent much of his life at sea with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Environmental Science and Services Administration, and finally NOAA. Collectively, he spent about 10 years on ships and 22 years working with the field parties.

If your ever had a question about “hydro” (i.e., hydrography), Shorty had the answer, most likely accompanied by the chapter and verse from the manual. After laying out the foundation of knowledge, he would promptly point you towards the manual for reading.

Just For Fun...

Shorty gets to work under the watchful eye of his colleagues, including Patches the dog.

Shorty was a singing, dancing, and ink-slinging hydrographer if there ever was one. With a little sand on the floor of our office trailer, Shorty would often launch into his own rendition of what he liked to call the “Train Dance.” He would start out slow, shuffling his feet back and forth, always flat on the floor, and, in perfect timing, he would gradually pick up speed. In a short time, you would have the audio pleasure of listening to that “locomotive” coming down the tracks. When he finally put the brakes on, he would let out a yell that would curl your hair as the steam settled near by. Everyone near him would laugh out loud, and his five-foot-three-inch frame would come to a halt.

Shorty was a man of many idiosyncrasies, you could say, from the way he stirred his coffee to his approach to entering and exiting a vessel. Together, the two of us formed a bond, as we both enjoyed sharing a practical joke (provided no one got hurt). He was 30 years senior to me, so I could easily be persuaded; he loved that and told me so. Shorty was from a lineage of men that were hard working and straight shooting. If they liked you, they would often tease you or set you in your place. If they didn’t care for you, they wouldn’t say much (and that would be your loss). It was always with the greatest respect for your task at hand that these comments were shared.

At Work on the Water…

Two hydrographers shoot a sextant fix for hydrographic surveying. Click image for larger view.

As green as I was at my introduction to the Field Parties, I did at least have practical knowledge of surveying from summer employment during high school. This was a big plus for me, as Shorty tagged me as an apprentice to his cartographic (map-making) skills. Although, I can assure you, I could never hold a candle to his capabilities.

There were no computers on the boats back then. In fact, the only electronic apparatus we had on the vessel was an echo sounder (fathometer). That machine would make you sick as a dog if you sat too close to it because of the way the needle burned the paper and the carbon would fly during the etching. You certainly wouldn’t want to let Shorty see you get “green,” because he was quick to point out that you didn’t look so good, all while he spoke about how he had some salt pork or lima beans in his lunch box…

During survey acquisition, Shorty would carry a plotting board on the boat, no matter if the boat was a 16-foot skiff or a 65-foot high-speed launch. With a three-arm protractor and a ditty box full of pencils and straight edges, Shorty would plot the course of the survey vessel’s position throughout the day’s activity. There was even a time when our positioning was acquired by sextant angles, which we would shout out to him as he charted the position on the “boat sheet.” This sheet was basically a rough draft of what would eventually become the “smooth sheet.”

After range/azimuth techniques were introduced, the course came much faster to Shorty, but he was always prepared for the next fix. When the launch coxswain started to veer off course, you would hear some grumbling in the seat behind you and, if you were at the helm, you had better be taking steps to correct your position. Before the days of “political correctness,” you might get a thump on the back of the head with a curled knuckle or the flicking of a forefinger on the ear from Shorty if it appeared you were not paying attention.

The Plotter in Action

On days when the weather kept us inside or as the survey neared completion, The Plotter went to work in a fashion as I have seen no other. Because there were no computers on the survey launch, all recorded soundings had to be written down by hand in a sounding volume. The soundings in this ledger were then reduced with predicted tides during post-processing, in preparation for Shorty to plot on the smooth sheet. This green federal volume would later be archived when the survey was submitted.

Shorty gets to work in plotting sounding data on the smooth sheet.

I would take a seat in close proximity to Shorty while he prepared his pens on a lighted chart table. When ready, he would ask you “how many between” (meaning the number of soundings between positions) and then, with 10 points, he would place the position numbers in blue ink. At the completion of the line, he would return to the beginning and ask for the soundings. As they were called out, Shorty would plot the soundings in black throughout the course of the line. Every digit was exactly the same size as well as character. When the sheet was finished, it was quite a piece of work. His technique and style were a wonder to behold.

In addition to the soundings, Shorty also used his cartographic skills to create “overlays” of the region to denote piers, piles, obstructions, and dangers to navigation. The great detail he put into these products was a reflection of how much he loved his work. Shorty was proud to be a part of the greatness of the Coast and Geodetic Survey, with its history dating back to 1807.

Remembering Shorty

Lloyd Gilden passed away in 2002, at the age of 83. Even after retirement in 1979, Shorty remained the adventurous traveler. He and his wife, Hilda, toured Alaska with their RV and visited our country’s greatest wonders. His tenure with the Coast Survey was legendary in my view, and the surveyors that knew him appreciated his wealth of knowledge.

As colorful a character as you have the pleasure of meeting if you are lucky in life, Mr. Gilden is now and will always be the embodiment of men and women that take upon the roles of cartographers and hydrographers to guide mariners with safe passage.

Contributed by David B. Elliott, NOAA’s National Ocean Service