NOAAmads: Life on a Hydrographic Field Party

Hydrography is the science which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of bodies of water and nearby land areas. Special emphasis is usually placed on the elements that affect safe navigation and the publication of information to enhance safe navigation. A hydrographic field party is a highly mobile unit designed to conduct near-shore surveys of U.S. coastal waters to maintain and update the national suite of nautical charts. Charts are essential for safe navigation of the ships that bring goods into and out of ports and defend our country.

The nomadic lifestyle has been a foundation of many civilizations throughout the centuries. That lifestyle continues today in the form of the National Ocean Service's hydrographic field parties. The chariots and chuck wagons of the past have been replaced by technologically advanced survey vessels and office trailers.

In the early days of hydrographic surveying, the echo sounder was the only type of "electronics" on a survey vessel and position was hand-plotted from sextant angles. Soundings were hand recorded in a sounding volume. The smell from the wire stylus burning carbon-based paper on the echo sounder was enough to make one queasy.

The NOAA Bay Hydrographer acquires hydrographic survey data in support of nautical charting. Click image for larger view and full caption.

Today, the obnoxious odor is gone, as are the sextants and the sounding volume. Computers now handle the task of plotting the vessel track and recording soundings in real-time as they are acquired. All of the information is displayed on dashboard monitors, including the bottom trace from the digital echo sounder.

Even though the instrumentation has become more automated, men and women on board hydrographic survey vessels still play an integral role in collecting and processing hydrographic data. These men and women make up today's hydrographic field parties. The story that follows provides a glimpse into life as part of a survey party, as a "NOAAmad."

On the Road...

One can only survey the same body of water for a finite period before moving on to the next body of water. Thus, hydrographic surveying work, by its very nature, is nomadic. This work can be accomplished by using ships, which are inherently mobile and essentially self-contained "cities" that deploy their survey vessels off the "mother" ship on a daily basis. Survey work can also be accomplished by hydrographic field parties which pull their equipment around the country using trucks and trailers.

Field parties are itinerant workers, not seasonal workers. So, while "normal life" may be an oxymoron when applied to field parties, it is nonetheless a desirable objective. To that end, spouses and children routinely travel with field party units.

The typical field party employee is tasked with moving government survey equipment from any point A to any point B, sometimes at a distance greater than 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers). He or she then hops on board an airplane at point B, returns to point A, and runs the trip all over again with personal vehicles, family, and gear.

On the road again...hydrographic field party members must transport equipment—such as boats—to each new survey site.

A new operations site and moorage for the survey vessel are located through a series of endless phone calls and a reconnaissance trip. Once at the new duty location, more logistics have to be arranged—from whether to stay in "permanent" housing or a campsite to deciding what associated utilities need to be obtained.

Field party members also must send off yet another phone number to friends and relatives, all of whom have allocated more than one page in their address books to keep track. The office trailer needs to be set up and the survey boat is launched and readied for survey operations...that is, once the basic psychological need of a roof over one's head has been met.

With the family ensconced in their new "home" and provided with a map of their new "hometown," and the children enrolled in their second school of the year, it is time to start surveying. Overall, the move from an old survey location to the new typically takes less than two weeks.

Daily Operations: Tools of the Trade

The crew meets at the office trailer each morning to discuss whether the day's operations will be on the water (weather permitting) or in the office trailer processing data (if inclement weather exists or is predicted).

A field party survey vessel "mows the lawn," transitting back and forth to collect data about the features of the ocean floor. Click image for larger view.

If the weather is suitable for a 30-foot survey vessel, a three-person crew heads out to the survey area. The team will have previously laid out a system of lines, similar to a farmer's corn rows, and is ready to deploy their arsenal of bottom investigation tools. These tools include a single-beam echo sounder used to determine the depth of the water directly below the boat, or, in more recent times, a shallow water multibeam system is used to determine water depths over a wider swath. A side scan sonar is used to search for any obstructions or wrecks in the survey area. The sonar beams look down and sideways from the centerline of the vessel track and cast a shadow behind any object resting on the bottom. The boat's position on the water is determined by a satellite-based global positioning system.

This setup is in great contrast to 50 years ago, when surveyors used lead lines to determine depth and either sextants on the vessel or shore-based personnel to locate the boat by measuring angles to the vessel. This process required at least five to six team members, versus the three members at work today.

Data Collection and Processing

While in transit to the survey area, a technician readies the onboard computer systems for data acquisition. Just short of the starting point of the first line to be run, the side scan sonar is deployed overboard, the person steering the boat (called the "coxswain") positions the boat on the line, and the technician begins data logging.

The rest of the day is spent "mowing the lawn," or transiting back and forth over the predetermined system of lines. Sensors are continuously monitored for shoal areas, wrecks, or obstructions, all of which will require further investigation to determine their extent.

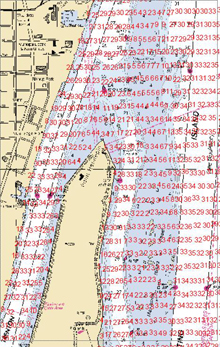

A survey example. The image shows acquired survey soundings, plotted in red, overlaid on the navigation chart of the survey area. The graphic also illustrates the line system used to conduct the survey. Click image for larger view.

By the end of the day, well over 30 miles (48 kilometers) of data have been collected. There has been a break for lunch, the brown-bag version, since the nearest restaurant is usually miles away. If hot soup is on the menu, placing it under the outboard engine cover usually delivers a tepid bowl of soup by noon. On the transit back to port, the data are readied and removed from the boat computer system for processing back at the office trailer.

A project for a body of water is divided up into "survey sheets," to make data handling more manageable. The average size of a sheet assigned to field parties takes approximately 400 nautical miles of data collection to complete. An entire project area can have well over 10 sheets. Survey statistics for a project can become staggering, with literally millions of soundings acquired. Imagine, 75 years ago, acquiring a million soundings by slinging a lead line! It would literally be a lifetime of work.

While many people labor on the assembly line, in the cubicle, or checking customers out at the retail giants, the daily grind for a hydrographic field party is on a boat. I'll take that over an office any day. Oh, as long as my wife does not mind...

Contributed by Brian A. Link, NOAA's National Ocean Service (and former NOAA Hydrographic Field Party Team Lead)