Isaac Monroe Cline: 1861 – 1955

NOAA's National Weather Service is the primary source of weather data, forecasts, and warnings for the United States and is the sole U.S. official voice for issuing warnings during life-threatening weather situations such as hurricanes. Using intricate computer modeling programs, a vast network of ground- and ocean-based sensors, satellites, and Hurricane Hunter aircraft, NOAA works to provide accurate predictions of hurricane storm track and intensity, helping to protect life and property.

- Introduction

- Cline's Early Weather Years

- Galveston Hurricane of 1900

- A New Focus

- A Lasting Legacy

- Works Consulted

While determined to provide all of his children with a proper education, it was Isaac who seemed to hold the most promise for John Cline. The boy's inquisitive nature and a penchant for doing things his own way began to surface before he could walk. In his autobiography, Cline recalls: "My inclination for research evidently developed at an early age; they said I investigated everything that came within my ken. Pottery jugs, with stoppers I could not remove, were broken – just to find out what was inside them."

Isaac Monroe Cline began his journey in this world in a two-room log cabin nestled in the Monroe County foothills near the Great Smoky Mountains of eastern Tennessee. As he neared the end of his life, 93 years later, he would look back on a time rich with triumphs and great tragedy. Following his birth on October 13, 1861, seven more little Clines would be born in quick succession to Isaac's parents, Mary and John.

Cline's inquisitiveness would eventually lead him to a career as one of the most accomplished and respected meteorologists of his time. But it didn't happen overnight. As a student in nearby Hiwassee College, Cline excelled in Greek, Latin, physics, chemistry, and mathematics. The question was: What to do with this education?

"I first studied to be a preacher, but decided I was too prone to tell big stories to be a preacher. Then I studied Blackman for a while, and soon learned that I was not adept enough at prevarication to make a successful lawyer. I then made up my mind that I would seek a field where I could tell big stories and tell the truth. Later, the weather furnished that field."

This article looks at Cline's accomplishments and how they contributed to a greater understanding of and ability to forecast our weather.

Cline's Early Weather Years

When the nation's weather service was launched as part of the Army Signal Corps in 1870, the commanding general determined it would be staffed with college-trained officers. Twelve years later, with the recommendation of Hiwassee College's president, 20-year-old Isaac Cline would become one of the officers. Stationed at Fort Myer, near the nation's capitol, Cline soon learned to march, handle weapons, ride horses, deliver and decipher military signals, and master the intricacies of telegraph and telephone technology. All of this training was leading up to the day when he would be recognized as an officer, a gentleman, and a meteorologist.

"Subjects bearing on meteorology, the taking and recording of meteorological observations, and the uses to which they could be applied, called for study every minute of our time. Good progress in studies meant early assignment as assistant observer on some station."

For Cline, that station turned out to be Little Rock, Arkansas. As an assistant weather observer, his duties were to take frequent daily observations, transmit the data to Washington, DC, and prepare bulletins for commercial use. A busy, but not overly demanding schedule, allowed time to pursue research in the field of medical meteorology. To that end, Cline enrolled in the Medical Department of the University of Arkansas. He earned his medical degree in 1885, and would devote much of the next 15 years to his chosen area of research.

From Arkansas, Cline headed west – where he would take charge of the weather stations in Fort Concho and Abilene, Texas. In 1887, he met and married Cora May Ballew of Abilene and their first child was born at year's end. Within two years, Cline, Cora, and three daughters would be on their way to Galveston – where Cline would be tasked with establishing a new weather station and organizing the U.S. Weather Service's Texas Section.

Quarters for enlisted men at Fort Concho, Texas (1871). Click image for larger view.

At the time, Galveston was a thriving commercial center and a popular vacation destination with a population of about 40,000. Located on a barrier island, 30 miles long and several miles wide, Galveston held the promise of becoming one of the biggest and most prosperous cities along the Gulf Coast. It was a promise destined to be smashed in a most violent and tragic fashion.

But that destiny was still in the future in July of 1891, when Congress transferred the service from the Signal Corps to the Department of Agriculture and renamed it the U.S. Weather Bureau. These were heady days for Texas Section Chief Cline, whose responsibilities and reputation seemed to grow apace.

During the late 1800s and through the turn of the century, Isaac Cline arranged for an exchange of weather observations between the U.S. Weather Bureau and the Mexican Weather Service, using Western Union and Federal Telegraphs of Mexico. Cline also produced and issued the nation's first 24- to 36-hour temperature forecasts and freeze warnings for farmers, and developed and used precipitation and stream-flow data to provide downstream flood warnings, saving many lives during an unprecedented Texas flood event in the spring of 1900.

The Galveston Hurricane of 1900

Cline's early experience with flash flooding in West Texas and the events of 1900 would prove invaluable again, in another time and another place. But in this time and in this place, Isaac Monroe Cline's world was about to be ripped from its moorings and tossed in a maelstrom of wind and water. Nothing would ever be the same again…

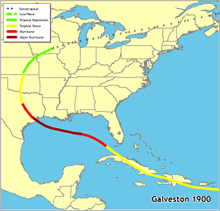

During the early evening hours of September 8, the worst of the great Galveston Hurricane of 1900 roared through the prosperous island city, with winds in excess of 130 miles per hour and a 15-foot storm surge. When its fury finally abated, at least 3,600 homes and buildings were destroyed and more than 8,000 people were killed.

This map shows the approximate path of the 1900 Galveston hurricane. Click image for larger view.

Despite the horrendous loss of life, many people were saved by Cline's actions that day. He and the Weather Bureau Headquarters staff were aware of the hurricane as it passed over Cuba on a northern track. Consequently, warnings were issued from Washington for the eastern Gulf Coast, Florida, and the southern Atlantic coast. But, once in the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane's track veered westward. Since wireless ship-to-shore communication was not yet available in 1900, information was extremely sketchy and there was no way of knowing the hurricane was strengthening and heading toward Texas.

As the storm neared the Texas coast, Cline became increasingly suspicious of the weather. Convinced that a major storm was pending, he decided to raise the hurricane warning flags atop the Galveston Weather Bureau building on September 7, the day before the hurricane struck. He had noted the sea swells were rising in size and frequency, a process that continued throughout the evening and into the early morning hours of September 8. At 5:00 a.m., neither the winds nor barometer readings gave any hint of trouble. But, Cline was now convinced the danger was near:

"Early on the morning of September 8th, I harnessed my horse to a two wheeled cart, which I used for hunting, and drove along the beach from one end of the town to the other. I warned people that great danger threatened them, and advised some 6,000 persons who were summering along the beach to go home immediately. I warned persons residing within three blocks of the beach to move to higher portions of the city…"

In 1900, the highest point in Galveston was only 8.7 feet above sea level and the hurricane rapidly inundated the city with a storm surge of 15 feet. Cline and his brother Joseph (one of several employees in the Galveston office) continued to report observations to Weather Bureau Headquarters in Washington, DC, until the last of the telegraph lines went down and all communication with the outside world was lost.

With nothing else to do, Cline waded through waist high waters to his home, where Cora May, their three daughters, and about 50 neighbors had taken refuge. Although the house was a stout structure, it was destroyed when struck by a railway trestle torn free of its moorings on the coast.

Buckled and broken homes line Galveston's streets after the 1900 storm. Click image for larger view.

While Cline, his three daughters, and his brother Joseph survived that terrible night, Cline's wife was among thousands who died.

As he looked back on the events of that day, Cline noted, "This being my first experience in a tropical cyclone, I did not foresee the magnitude of the damage it would do." Convinced that people could be warned in time to move out of tropical cyclone danger zones, he found a new focus for his research, which would have significant ramifications for future forecasters and the public.

"I decided that I could be of greater service to humanity by determining what are the physical forces in the cyclones that develop the storm tides and by devising rules for use in forecasting and warning the public in advance of their arrival – than I could by continuing my medical investigations."

A New Focus

In August of 1901, Cline and his children moved to New Orleans, where he would assume the duties of forecaster-in-charge of the recently created Gulf District. His forecasting responsibility was extended beyond Texas and Oklahoma, to include the states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, and northwestern Florida. Now situated in coastal Louisiana, along the banks of the Mississippi River, he was in a prime location to further his research into tropical cyclones and to demonstrate the efficacy of his flood-forecasting capabilities.

Cline successfully predicted, two weeks in advance, the major stages of the Great Flood of 1927. Click image for larger view and complete caption.

Frequently at odds with Washington-based forecasters, Cline persisted in providing the region's citizens with flood forecasts based on his own calculations using precipitation and stream-flow data. These forecasts were usually issued in defiance of headquarters' policy and earned him considerable criticism from many of his East Coast colleagues. The criticism faded over time with the accuracy of his predictions during the floods of 1903, 1912, and the great Mississippi River flood of 1927.

Throughout this same period, Cline persisted in his studies of tropical cyclones. Between 1900 and 1924, he meticulously charted meteorological data observed during 16 cyclones affecting the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. He was personally involved with 10 of those storms and his work dramatically advanced tropical cyclone forecasting methodology. Prior to his work, cyclone studies were based primarily on broad synoptic charts with little support from observation data. In contrast, Cline's method determined the storm's probable path by observing minimum air pressure and wind shifts recorded at stations ahead of and to the sides of the cyclone. He then plotted the track on a map indicating hourly positions, wind and cloud directions, wind speeds, and precipitation.

Cline published his research on tropical storms in a book called Tropical Cyclones in 1926. In a review published four years later in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, it was said that: "This book constitutes a notable advance in the collection and representation of precise data with regard to tropical cyclones of the North Atlantic Ocean, observed at coastal and inland stations of the American continent." Widely recognized as a landmark achievement in weather research, his book soon became a "must read" text for aspiring meteorologists throughout the world.

A Lasting Legacy

In 1935, Isaac Monroe Cline, M.A., M.D., Ph.D., retired from the U.S. Weather Bureau. His was a legacy of outstanding public service, innovative forecasting and invaluable contributions to the science of meteorology. Dr. Cline would live another 20 years, pursuing his former avocation as an art dealer in the famed French Quarter of New Orleans.

Like other dedicated pioneers who lived before and after him, his work was instrumental in laying the foundation for the scientific and technological advances epitomized by today's National Weather Service and its parent organization, NOAA.

Contributed by Ron Trumbla, NOAA's National Weather Service

Works Consulted

Cline, I.M. (1945). Storms, Floods and Sunshine. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Co. Inc.

Heidorn, K.C. (2000). Dr.

Isaac M. Cline, Part 3, New Orleans: Watching A River. Retrieved

August 21, 2006, from

http://www.islandnet.com/~see/weather/history/icline3.htm

Larson, E. (1999). Isaac's Storm. New York, N.Y. Crown Publishing Group.