Coastal Ecoystem Research

The National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science conducts and supports research, monitoring, assessments, and technology development to meet NOAA’s coastal stewardship and management responsibilities. Coastal ecosystem research ranges from the study of biomolecular changes due to coral bleaching, to the causes of shellfish disease, to modeling the effects of climate change on fisheries stock assessment. The research is broad, multi-disciplinary, geographically diverse, and involves many partners. The overall goal is to improve the scientific basis upon which coastal managers make decisions.

This Pacific Northwest coastline is one example of the many ways land meets the ocean. Many complex interactions take place on these boundary areas: chemical, geological, and biological. Every coast is unique. Click image for larger view.

Our nation’s coastal and ocean resources are vast, encompassing 95,000 miles of Atlantic, Pacific, and Great Lakes coastline; 150,000 square miles of marine sanctuaries; around 23,000 square miles of coral reefs; and over 2,000 square miles of estuarine reserves.

NOAA works closely with federal, state, and local partners to develop and implement effective policies and management plans to protect, preserve, and ensure the long-term health and use of these resources. Developing such management strategies and determining their effectiveness requires close monitoring and understanding of coastal areas. Since its establishment in 1970, NOAA’s coastal scientists have made great strides in studying coastal ecosystems.

Ecosystem condition is determined by the interaction of climate change, pollution, invasive species, land and resource use, and extreme events. To better understand these conditions, NOAA is building a program to inventory species, assess conditions, monitor trends, and predict changes in U.S. ecosystems.

NOAA ecosystem research builds on and links to existing federal, state, and territorial monitoring efforts, providing decision-makers with key information to respond to changing environmental conditions, assess the effectiveness of existing management strategies, and identify the need for additional protective measures.

This article examines how NOAA’s activities in coastal ecosystem research, monitoring, assessment, and technology development for managing coastal ecosystems and society's use of them, have evolved over the past three decades.Estuaries: Where Rivers Meet the Sea

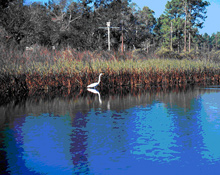

Estuaries provide buffers against coastal storm impacts and nursery areas for many commercial and recreational fish. Click image for larger view.

Estuaries are places where freshwater from land mixes with saltwater from the sea. They are also the foundation for much of ocean life, providing nurseries for fish and food and shelter for shorebirds. Estuarine vegetation filters sediments and absorbs nutrients from water flowing in from upstream, and moderates the impacts of storms.

Estuary research at NOAA is focused on increasing the understanding of these complex coastal systems and improving the ability to protect and restore estuarine habitats.

National Status and Trends Program

Since 1984, NOAA has conducted the largest and most comprehensive national monitoring program of coastal marine environmental quality ever undertaken in the United States: the National Status and Trends Program. The status and the long-term trends in environmental quality in estuarine and coastal areas is monitored by measuring levels of toxic chemicals in bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters (bivalves), and sediments.

The Mussel Watch Project, one component of the National Status and Trends Program, began in 1986 with sampling at 150 sites. Today, the Mussel Watch Project is the longest running continuous contaminant monitoring program in U.S. coastal waters. The trends in chemical and biological contaminants in sediments and bivalve tissue from over 280 coastal sites are now monitored.

Data from the Mussel Watch Project has helped document the effectiveness of environmental legislation passed in the 1970s and 1980s on estuarine and coastal environments. The efficacy of the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Organotin Antifoulant Paint Control Act are evident in the results of this long-term monitoring project. NOAA has consistently analyzed mussels and oysters from specific locations around the country for over 20 years. These shellfish are ideal for monitoring contaminants because they remain in the same place over a long period and accumulate contaminants in their bodies at a known and consistent rate.

The versatility of these data became apparent when they were used to determine possible contamination of aquatic environments resulting from the September 11, 2001 collapse of the World Trade Center and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005.

National Estuarine Research Reserves

Marshes filter many pollutants and excess nutrients from the land before they make it to the ocean. Click image for larger view.

The Coastal Zone Management Act, enacted in 1972, greatly affected estuary science and protection. The Act called for the funding, establishment, and maintenance of National Estuarine Research Reserves, or NERRs. The reserve system is a partnership between NOAA and coastal states that has protected more than 1.3 million acres of coastal and estuarine habitat at over 27 sites since the program was established.

Research is a key component of the reserve system. In 1995, NERRS scientists established the System-wide Monitoring Program (SWMP) to coordinate data and research among the reserves. Today, the SWMP measures a range of water quality and weather parameters, such as water temperature, salinity, and wind speed and direction. Observations are collected every 15 minutes and are published on the Internet.

Coral Reefs: Rainforests of the Sea

U.S. coral reef ecosystems cover less than one percent of the Earth’s surface, yet are among the most diverse and productive communities on the planet. Reefs enhance biological diversity, fisheries, tourism, maritime and cultural heritage, and protect shorelines from storm damage. Stressed by human activities and extreme natural events like hurricanes, coral reefs are in decline worldwide. Excess nutrients and sediments, over-fishing, coastal development, and increased coral bleaching from abnormally warm water threaten nearly 60 percent of the world’s reefs and the resources they support.

Sound management of coral reef ecosystems requires scientifically based information on their condition, the causes and consequences of that condition, forecasts of their future condition, and the costs and benefits of possible management actions to maintain or improve the condition of corals. NOAA mapping and monitoring programs record changes in ecosystem conditions, whereas research illuminates the causes and predicts the impacts of those changes.

Coral reefs serve as habitat for many fish species. Click image for larger view.

NOAA scientists develop computer and remote sensing technologies to map coral reef ecosystems inexpensively and with increased speed and accuracy. Using these technologies, NOAA leads federal efforts to map all U.S. coral reefs by 2010. The maps provide the spatial framework to design and implement research programs and the capability to effectively communicate information to ecosystem mangers.

NOAA coastal scientists are also coordinating the scientific resources of the U.S. and its territories through the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force’s Coral Disease and Health Consortium. Research programs examine the effects of disease and environmental stressors, and how they impact the health of coral reef ecosystems. Research on the biomolecular mechanisms of coral bleaching will allow managers to forecast bleaching events and mitigate conditions threatening coral health.

Coastal Ocean: Where the Land Meets the Sea

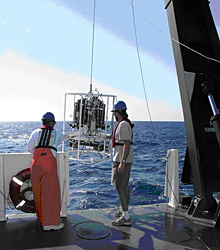

Scientists deploy instruments to collect water column samples and measure salinity, depth, and temperatures. Click image for larger view.

The coastal ocean encompasses a broad range of saltwater ecosystems, including estuaries, coral reefs, rocky shores, gravel shores, sandy shores, mud flats, marshes, and mangrove forests. At least two-thirds of the nation’s commercial fish and shellfish use these ecosystems as spawning grounds and nurseries. In addition, the wetlands associated with estuaries buffer uplands from flooding. Coastal areas also provide many recreational opportunities, which contribute to a community’s economic health. NOAA participates in a range of research activities to understand these ecosystems.

Sanctuaries

A century after the establishment of the first national park at Yellowstone, Congress passed the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972. It stipulated that a network be created similar to the National Park System, protecting near-shore and offshore areas of national concern. NOAA was responsible for identifying, designating, and managing marine sites based on conservation, ecological, recreational, historical, aesthetic, scientific, or educational value within significant ocean and Great Lakes waters.

The Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary is dedicated to protecting humpback whales and their environment. Click image for larger view.

The first sanctuary designated under the Act was the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary, which protects the historic remains of the USS Monitor, a famous sunken Civil War ironclad ship rediscovered in 1973 off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Over the next 33 years, twelve additional marine sanctuaries and one marine national monument were added. The latest addition is the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, the largest protected area in the world.

Since 1999, NOAA coastal scientists have been working with staff from the National Marine Sanctuary Program (NMSP) to effectively manage our marine sanctuaries using the best available science. Key to this work is providing a research perspective in creating sanctuary management goals. Working with NMSP staff, scientists from the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS) are designing and implementing new research projects and integrating ongoing studies to understand the status and trends of sanctuary resources and human uses within sanctuaries. Projects focus on essential habitat identification, biodiversity, and conservation.

NCCOS conducts this research and provides science-based recommendations on the consequences of management actions on sanctuary resources and management goals.

Harmful Algal Blooms

Over 50 percent of the unusual marine mammal mortality events are due to harmful algal blooms. Click image for larger view.

One of NOAA’s major efforts in coastal science is studying harmful algal blooms or HABs. Algae, tiny free-floating organisms, are naturally present in nearly all water. When the conditions are right, they can reproduce quickly, resulting in a population explosion. Often these are harmless. However, certain algal species produce poisons, which may protect them from being eaten by other marine organisms. When the algae are in normal numbers, the toxins they produce are too dilute to do harm, but when concentrated in a HABs event, these toxins can cause temporary or permanent damage, even death, to organisms that encounter them, including humans.

NOAA scientists have been monitoring and studying HABs to determine how to detect and forecast the location of the blooms. The goal is to give coastal communities advance warning, so they can adequately plan and deal with the adverse environmental and health effects associated with a harmful bloom.

HABs are costly not only to human health, but to the economy, as well. Presently, HABs cause about $82 million in economic losses to the seafood, restaurant, and tourism industries each year.

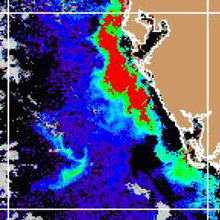

Satellite imagery, such as this image of a HAB event off the west coast of Florida, are used in preparing HABs forecasts.

In 1987, NOAA developed the CoastWatch Program. CoastWatch was the first application of satellite data and oceanography on an operational basis. CoastWatch continues to ensure timely access to near real-time satellite data and products.

However, monitoring algal blooms is not enough. To protect the public, it is also necessary to predict where and when a bloom will appear, in the same way that weather forecasters predict thunderstorms or other weather events. Since 1999, NOAA has been working with federal and state agencies that manage HAB monitoring and impacts in the Gulf of Mexico. Outbreaks caused by toxic blooms occur nearly every year on the Florida Gulf coast. NOAA and its partners transformed data into an ecological forecast system for HABs in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. This forecast system is a scientific breakthrough for understanding, monitoring, and forecasting HABs.

Ecological Forecasts

By translating scientific results into “ecological forecasts,” NOAA provides coastal managers with scientifically sound information and management tools and techniques. Ecological forecasts are similar in theory to the better known weather forecasts. These forecasts inform what future ecosystem conditions might be like. Ecological forecasts give managers the tools to answer “what-if” questions about the ocean and coastal environments. Predicting the consequences of different activities on the ocean and coastal environments helps managers take specific actions that balance the multiple demands on these environments.Ecological forecasts bring together wide-ranging research and observations. Forecasting is a new and challenging science focused on projecting conditions that may harm coastal environments and resources. It integrates physical, chemical, biological, economic, and social data about the current condition of the coastal environment and predicts future conditions, based on different management strategies.

These forecasts allow managers to decide what future conditions are acceptable to society and to take appropriate actions to affect those conditions, providing a bridge between research science and governmental policy.

Conclusion

From monitoring shellfish, to protecting valuable fisheries, to making beaches and seafood safe, our nation depends on the many sentinels who work closely together with the help of NOAA's coastal ecosystem scientists. Targeted research is essential for assuring resource managers have the information needed for a healthy coastal environment.