Toxic Tides: The 2005 New England Harmful Algal Bloom

As the federal agency largely responsible for overseeing the nation's marine resources, NOAA is working to find out what causes harmful algal blooms and how they can be predicted and prevented. In May of 2005, NOAA's harmful algal bloom prediction and response capabilities were put to the test when a massive bloom spread along the New England coast.

- Introduction

- Impacts of Harmful Algal Blooms

- The 2005 New England Bloom

- NOAA Aids Response

- Working to Enhance Predictions

- Works Consulted

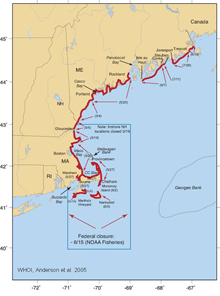

Shellfish closures due to Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP) toxins during the 2005 Alexandrium bloom are shown in red along with closure issuance dates. The temporary federal closure of adjacent offshore waters is indicated by the blue rectangle. Click image for larger view and image credit.

If you ever headed to the beach or to a shellfish bed to collect oysters, only to find that it was closed due to a “red tide” or toxic levels of algae in the water, you have encountered a harmful algal bloom. These blooms occur when algae, simple plants that live in the sea and form the base of the food web, produce toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds.

In the summer of 2005, the most severe bloom in over 30 years spread from Maine to Massachusetts, resulting in fishery closures in areas that had not been impacted in previous outbreaks. Such blooms occur periodically in the Gulf of Maine, but rarely at the density and geographic extent witnessed during 2005. NOAA support over the last decade has advanced understanding of blooms in New England and allowed more effective prediction and response, a fact that was evident during the historic 2005 event.

Background: Some Impacts of Harmful Algal Blooms

The algae Alexandrium fundyense is one of several algal types that create blooms often called “red tides,” but more correctly referred to as harmful algal blooms, or “HABs.”

Signs such as this one signal the closure of shellfish beds contaminated during harmful algal bloom events. Image courtesy from J. Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Alexandrium produces potent neurotoxins that can accumulate in filter-feeding shellfish such as mussels, oysters, and clams. Eating toxin-contaminated shellfish can lead to Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP), resulting in severe illness or death in humans. Alexandrium blooms occur periodically in the Gulf of Maine, and states in the region maintain rigorous shellfish monitoring programs in coastal waters to prevent outbreaks of PSP.

HABs are costly not only in health terms but in economic ones as well. They are estimated to result in economic losses of at least $82 million in the fisheries, public health, tourism, and management sectors each year. HABs reduce tourism, close beaches and shellfish beds, and decrease the catch from both recreational and commercial fisheries. They also have significant environmental and sociocultural consequences, which have significant “costs” but have not been well quantified in economic terms.

The 2005 New England Bloom

Alexandrium under the microscope. Image courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

In 2005, the most severe bloom of Alexandrium fundyense since 1972 spread along the New England coast. Scientists suspect that elevated rainfall and snowmelt in the spring, followed by two unusually late Nor'easters and increased runoff in May, fueled the outbreak by creating ideal conditions for algal growth.

This historic bloom extended from Maine to Massachusetts and resulted in extensive, and in some areas, unprecedented, closures to commercial and recreational shellfish harvesting to protect humans from PSP. State closures along the New England coast began as early as mid-May, disrupting shellfish sales during the busiest period of the tourist season. In Maine and Massachusetts alone, economic losses due to lost shellfish sales were estimated at $11 million.

In June 2005, NOAA instituted a temporary closure of 15,000 square miles (38, 850 square kilometers) of federal waters at the request of the Food and Drug Administration. NOAA also declared a “Fishery Failure,” to allow emergency disaster relief for the region’s commercial fishermen.

NOAA Aids Response

Decade of NOAA-supported Research Enhances Response

NOAA and the National Science Foundation, through the interagency Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms (ECOHAB) program, have funded a decade of research on Alexandrium in the Gulf of Maine, to increase understanding of bloom ecology. This research, coupled with research funded through the NOAA Monitoring and Event Response for Harmful Algal Blooms (MERHAB) program, has enhanced event response, forecasting, and mitigation capabilities for coastal managers.

For example, these programs have led to new methods based on molecular biology that are used to rapidly detect and map Alexandrium blooms. These data provide early warnings to coastal managers, and when combined with oceanographic and meteorological data from ships and moorings, can be used in recently developed biological and physical models. These models were used to forecast bloom movement and to understand the factors leading to the 2005 New England bloom event.

NOAA Assists Managers During Bloom Events

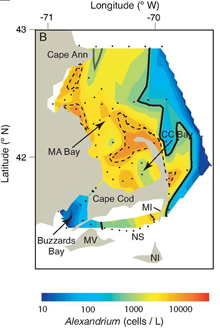

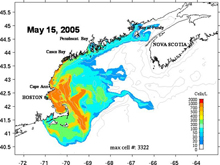

Contour plots show the distribution of Alexandrium cells as estimated using molecular probe technology during June 2-4, 2005. Click image for larger view and full caption.

NOAA responded to the 2005 New England HAB by providing emergency funding for new and expanded sampling of the toxic algae in Massachusetts Bay. This emergency funding allowed monitoring of algae abundance and the extent and movement of the bloom. Researchers were also able to collect fish and zooplankton, to investigate the potential transfer of toxins via the food web and whale mortalities in the region.

Expansion of shellfish closures to Buzzards Bay, Nantucket Island, and Martha's Vineyard raised concerns that Alexandrium could move into southern New England and New York waters, resulting in additional shellfish closures. To address these concerns, supplemental funding was provided to support cruises for continued monitoring of bloom movement.

NOAA: Working to Enhance Future HAB Predictions

Using measurements taken from New England waters during the bloom, researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution produced a computer-modeled “hindcast” of the 2005 bloom. Click image for larger view, image credit, and full caption.

NOAA awarded additional funds to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to monitor HABs in New England throughout the 2005 bloom period and again in 2006. This funding also supported post-bloom research in order to improve HAB forecasting in New England and to enhance the efficiency of future monitoring and regulation.

One goal of the research is to understand this particular event by using the model to reproduce or “hindcast” the event. Hindcasts help scientists understand the critical factors that cause blooms, which will improve future forecasts.

In addition, because future forecasts will be influenced by Alexandrium’s resting cysts, which are deposited on the seafloor at the end of a bloom and will seed future blooms, scientists mapped new cyst distributions for incorporation into predictive models. These models will aid bloom forecasting in future years.

Works Consulted

Anderson, D.A., Keafer, B.A., McGillicuddy, D.J., Mickelson, M.J., Keay, K.E., Libby, P.S., Manning, J.P., Mayo, C.A., Whittaker, D.K., Hicky, J.M., He, R., Lynch, D.R., & Smith, K.W. (2005). Initial observations of the 2005 Alexandrium fundyense bloom in southern New England: General Patterns and Mechanisms. Deep-Sea Research II. v. 52 (19-21), p. 2856-2876.