Exploring the South Pacific: Witnessing the Birth of an Undersea Mountain

NOAA's Undersea Research Program (NURP) provides scientists with the tools and expertise they need to investigate the undersea environment, including submersibles, remotely operated vehicles, autonomous underwater vehicles, mixed gas diving gear, underwater laboratories and observatories, and other cutting-edge technologies. NURP also provides extramural grants to both the federal and non-federal research community.

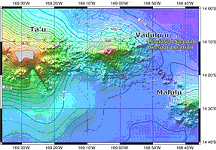

NOAA's Undersea Research Program, in collaboration with NOAA's Office of Ocean Exploration, focused their work on the 2,000-mile stretch from Hawai'i to Samoa that contains a series of American Flagged protectorates. Click image for larger view and full caption.

Since the formation of NOAA’s predecessors 200 years ago, survey vessels have documented the underwater relief of our nation’s coasts and nearshore ocean environments. However, much of the South Pacific oceans still remain scientifically unexplored. Very few deep submergence research missions have reached this undersea landscape, due to the limitations imposed by distance from land, water depth, and availability of resources.

In the summer of 2005, the Hawai‘i Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL – a joint program between NOAA and the University of Hawaii), NOAA's Undersea Research Program (NURP), and NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration conducted the most extensive diving expedition ever undertaken in the South Pacific. This pioneering mission looked at some of the greatest undersea volcanoes and associated ecosystems between Hawai‘i and New Zealand, including Nafanua, Fagatele Bay, and Rose Atoll.

HURL operates two of only nine currently available deep-diving research submersibles in the world: the submersibles Pisces IV and Pisces V. During the five-month expedition, the submersibles dove to depths of 2,000 meters, carrying a pilot and two science observers. The submersibles spent six to eight hours on the bottom, taking photographs and collecting samples and key in situ measurements.

What these scientists discovered was truly amazing…

Nafanua: Birth of a New Island

Map showing the location of Vailulu‘u Seamount in relation to American Samoa.

NURP's first project concentrated on American Samoa. Work here consisted of a series of dives led by Dr. Hubert Staudigel of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Dr. Craig Young of the University of Oregon, focusing on the Samoan volcanic hot spot at the Vailulu‘u seamount.

Geology

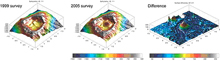

The Samoan chain forms the northern end of the Kermadec Arc, which volcanically expresses itself in the hot spot seamount of Vailulu‘u. This is a very active hot spot with no previous submersible investigations. The seafloor around Vailulu‘u had been mapped, but a great surprise was in store for the research team: In the six years since the most recent mapping, a 300-meter-tall volcanic cone, known as Nafanua, had grown in the summit crater.

Before, after, and difference map of the Vailulu‘u crater and the newly formed Nafanua cone within it. Click image for larger view and image credit.

This incredible level of growth could mean that the Vailulu‘u Seamount will breach the sea surface within decades, forming a new island in the Samoan group. Culturally, the birth of such an island is a very revered event in Polynesian society.

Biology

Researchers found that Nafanua's cone area was very active, with several distinct types of hydrothermal venting. This activity in turn produced a range of unique biological habitats. Low-temperature hydrothermal vents produced iron oxide chimneys and one-meter thick microbial mats. There were also a series of higher-temperature vents that were much less benign. These vents spewed toxic acid waters of low salinity that had temperatures of about 185°F (85°C) and contained oily looking droplets of immiscible carbon dioxide. These venting areas and the 'moat' at the base of the new cone were almost devoid of macroscopic life.

The fluids in the deepest parts of the volcanic basin were evidently so toxic that the base of the new cone was scattered with the carcasses of fish and mollusks that apparently died from the exposure. Scientists did find, however, one species of bright red worm (hesionid polychaete) feeding on or near the carcasses. This is an interesting adaptation and a clear indication that Vailulu‘u has much to offer as a natural laboratory for the study of a complex bottom (benthic) habitat.

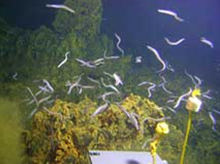

"Eel City" swarms with foot-long Dysommina rugosa at the Vailulu'u Seamount, American Samoa. Click image for larger view.

Sponges of several sorts feeding on microbes of vent origin dominated the inner wall of the volcano. The outer volcano walls were scattered with octocorals, sponges, and occasional asteroids, ophiuorids, and crinoids feeding on oceanic plankton.

At the summit of Nafanua, researchers discovered a thriving population of eels (Dysommina rugosa), each about a foot in length. In fact, there were so many eels congregated at a single vent location that the area was referred to as “eel city” by the submersible pilots. Habitat analysis by Dr. Young showed that this large eel community survived on crustaceans that floated down from the water column above. Apart from the abundant eels, the only two other organisms found near the summit vents were a copepod and a scale worm.

Taema Bank and Fagatele Bay

Deep reef at Taema Bank, American Samoa. Click image for larger view.

Dives on the highly active hot spot volcano were followed by a series of dives by Dr. Dawn Wright in the Eastern Samoan islands, on Taema Bank and at Fagatele Bay, off the island of Tutuila. Dr. Wright’s goal was to map pristine benthic habitats, to “ground-truth” previously made seafloor maps of very sensitive biological areas. The work supports a major American Samoa government initiative to designate “no take” zones within pilot marine protected areas. Areas of 20 percent or greater coral cover are mandated for special protection.

Fagatele Bay is an especially sensitive National Marine Sanctuary. This small bay and adjacent canyon were subject to a devastating infestation of Crown of Thorns starfish in the late 1970s, as well as several hurricanes and a severe coral bleaching event in 1994. The Sanctuary is now well on the way to recovery, but stringent management protocols are needed to continue the recovery process.

The NURP submersible work was able to identify biological “hot spots,” verify key benthic habitats from previous terrain maps, and photograph and video a far wider range of deep marine life than previous SCUBA studies had been able to ascertain. At least nine of the species identified in the dive work were new records for Samoa.

Additionally, two secondary school teachers were brought on the cruise as observers. They will be using the photos, videos, and maps provided by the science team directly in their classrooms to educate and inspire students who otherwise would never have access to the deeper marine world right off their coast.

Rose Atoll

Top: Gold coral colonized by two red crinoids at Kingman

Reef ( Line Islands).

Middle: Pisces IV collects a coral sample at Palmyra Atoll.

Bottom: Pisces V with a basket of coral samples at Kingman

Reef, as viewed from the Pisces IV.

A day's sail east of the main Samoan Islands is the Rose Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, which was established in the 1970s. Rose Atoll is a pristine reef. At some point, the reef may be nominated as a world heritage site, a UNESCO-driven process that links the concepts of nature conservation and the preservation of cultural properties. Unfortunately, this pristine reef was the site of an October 1993 grounding and breakup of the Taiwanese fishing vessel Jin Shiang Fa. Initially, the shallow reef was examined for the effect of this ship grounding.

After some early salvage attempts, the ship's bow section, which was separated from the rest of the vessel, was towed off the reef and dumped into deeper water. There had been concern that the bow section was stuck on the reef at a depth of less than 300 meters and would negatively impact the reef with iron dissolution and other pollution from continued breakup.

The work with HURL was done by Drs. Michael Graves and Suzanne Finney of the University of Hawai'i and Dr. James Maragos of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Pisces submersibles surveyed the reef to a depth of 941 meters, finding no evidence of the bow and very few cultural artifacts. It appears the atoll may not require additional cleanup efforts offshore and that these efforts can be redirected to monitoring the lagoon and marine-facing reefs.

During the dive, high levels of biodiversity were also found at depth. Scientists identified as many as 60 new or rare species of marine life. The excellent dive photographs and video documentation of life on this unique atoll will greatly help the process of nomination and successful designation of Rose Atoll as a World Heritage Site.

Conclusion

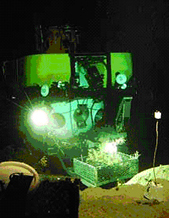

Pisces V, secured to the back deck of Ka‘imikai-o-Kanaloa (KoK), rides out some bad weather and rough seas.

The five-month South Pacific expedition represents HURL's longest and most successful cruise in its 25-year history. As a result of the cruise, scientists gained a deeper understanding of many of the processes that form islands and change their benthic habitats – especially given that none of these areas had ever had any systematic deep-diving or submersible investigations. This information will help maximize efforts to protect many of these threatened and pristine environments in the South Pacific.

A follow-up submersible expedition to revisit some of these critical sites is already in planning for 2008-2009.

Contributed by John Wiltshire and Felipe Arzayus, NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research