Again to Galapagos

Over the past few decades, we have significantly increased our understanding of, and ability to explore, the ocean. Although we are increasingly aware of our dependence on the ocean for the oxygen we breathe, regulation of temperatures to make the planet livable, healthy fisheries, a source for new medicines and answers to questions about global climate, 95 percent of the ocean remains unexplored. NOAA, through the Office of Ocean Exploration, is leading federal efforts to increase understanding of our ocean.

When I staff an exhibit booth for NOAA's Office of Ocean Exploration, I sometimes gather audiences by asking a question. First, I announce, "There are robots going to Mars and elsewhere in space looking for signs of life that may be very different from us—alien life." Then I ask, "Do you think we'll find it? Alien life? Life different from us?"

A size comparison of the young, small clams found at the Rosebud site during the 2002 ocean exploration mission, and the large, adult clams found at the newly discovered vent site 200 miles west of Rosebud, along the Galápagos Rift. Image courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Quite a few little discussions go on, resulting in a good number of head-nodding "yes" answers, but there's the "no" crowd, too. "Guess what," I ask rhetorically while focusing on the children in the group, "we already have, not on Mars but right here on our own planet—in the ocean—in 1977." (This is where my voice gets creepy) "And right now, you are standing less than five feet from alien life different from you."

Some look at the person next to them, and others look at me. "It's not me," I'm quick to add, "it's this guy right here." I point to a really large clam shell on the table in front of me that had gone unnoticed. People in the back move a little closer, but nobody gets real close. Everyone seems interested in the story, and so I continue. "Until 1977, we thought all life on Earth was like us—life based on sunlight—photosynthetic life. But, in 1977, ocean scientists discovered new animals living around hot springs that flowed from cracks in lava on the sea floor. Far from sunlight, these new animals had lives based on chemicals—chemosynthetic life."

An Alien Discovery

What scientists discovered was stunning, and something so new, it was arguably one of the most significant discoveries in modern science. It forever changed our understanding of our planet and life on it. Kathy Crane was one of those scientists. Now a Program Manager in NOAA's Arctic Research Program, Kathy was a graduate student in 1977 assigned as navigator for the manned submersible Alvin, on the first submersible expedition to the Galapagos spreading center. She also dived in Alvin as one of the few who had first-ever views of the strange new life around hydrothermal vents in "Rose Garden," named for the area's colorful variety of life.

In Rose Garden, Kathy collected samples of bacteria that lived symbiotically in giant tubeworms, mussels, and clams, where they processed toxic chemicals into sugar to nourish their hosts. Kathy's experience is one among many described in the book, "Sea Legs," her account of her life as a woman oceanographer.

A Return Mission: 2002

In May and June 2002, to mark the 25th anniversary of the historic discovery of chemosynthetic life, a team of scientists from NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and several universities revisited the Galapagos Rift. Their technology again included the workhorse deep submergence vehicle Alvin, but they also brought new technology in the form of the Autonomous Benthic Explorer and digital camera systems for night-time remote surveying. The scientists and explorers created new, high-resolution maps of the area; collected biological and mineral samples; and explored for other sites of hydrothermal activity.

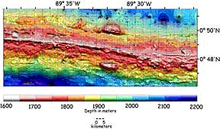

This is a multi-beam bathymetric map of the area investigated during the 2002 expedition. Colors show the depth to the sea floor in meters. Blue colors are deeper depths and pink to white colors show the shallow area along the ridge axis. Map produced by Dan Scheirer.

The team filed daily logs from sea that were posted on the NOAA Ocean Explorer Web site, updating students, teachers, and armchair explorers who became "virtual" team members. Also on the Web site are lesson plans for teachers, all of which are tied to the expedition and to National Science Education Standards. The lessons boast names such as, "Why Do We Explore," and "AdVENTurous Findings." One lesson plan, created in advance of the mission and named, "Who Promised You a Rose Garden," was a bit of a bad news fortune teller…

Rosebud

Steve Hammond from NOAA (left) and Tim Shank from Woods Hole were co-principal investigators for the 2002 Galapagos mission. Tim provided NOAA with the chemosynthetic clam specimen mentioned earlier in this article.

A key objective of the 2002 cruise was to compare the present state of the famous Rose Garden hydrothermal vent site to the way it was in 1977. The team searched for the Rose Garden vent field; however, the vent field was gone, apparently covered by a lava flow. While the team searched in vain for the vent field, they discovered a new community of hydrothermal animals that seemed the likely beginning of a "reborn" Rose Garden. Aptly, they named the site "Rosebud."

It is certain that the Galapagos has more stories to tell, and scientists on NOAA-supported expeditions in late 2005 and early 2006 searched for more answers. In May and June 2005, Tim Shank and Dan Fornari from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution joined with others to research hydrothermal vents at Rosebud. It was Shank who obtained the giant clam specimens in 2002 and who shared some of these specimens with NOAA's Ocean Exploration office.

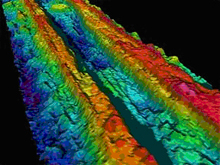

This bathymetric map was created during the most recent mission in 2005, "GalAPAGoS: Where Ridge Meets Hotspot," using the EM-300 multi-beam sonar. The image shows the ridge crest at four times greater resolution than the previous bathymetric map from 2002. Seeing the Galapagos ridge in greater detail enhances our ability to interpret the geological processes that contribute to shaping the ridge. Image courtesy of the University of California – Santa Barbara, University of South Carolina, NOAA, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Returning to Rosebud, Shank said, "There's no other place on the planet like this, yet we know little about how young organisms colonize, assemble, and form new communities."

Biologists studied how larger animals at the site evolved since the 2002 mission, and they compared the genetic composition of those animals with genetic data from samples of sea-floor larvae. Microbiologists used genetic techniques to study microbe samples taken from rocks and vent animals. Geologists collected rock samples and used data from Alvin to make sea-floor maps, including the lava flow that had covered the Rose Garden.

The Search for Black Smokers

In December 2005 and January 2006, a mission led by University of California at Santa Barbara Professors Rachel Haymon and Ken Macdonald, and funded jointly by NOAA and the National Science Foundation, explored a 400-kilometer-long section of the Galapagos Spreading Center located above the mantle plume that created the Galapagos Islands. This area was completely unexplored for hydrothermal vents and other fine-scale sea-floor features. Using towed near-bottom sonars, hydrothermal plume sensors, and cameras, explorers sought to uncover hydrothermal, geological, and biological responses to magma supply and crustal thickness.

The cruise was also jointly led by Ed Baker and Joe Resing of NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL), who used instruments nicknamed MAPRs (Miniature Autonomous Plume Recorders; pronounced “mappers”) and developed at PMEL a number of years ago for surveys of this type. Those instruments discovered the Galapagos vent fields that were subsequently imaged by camera tows. MAPRs are small (about the size of a thermos bottle), lightweight, simple to use, self-contained, and carry the basic sensors necessary for identifying hydrothermal plumes: pressure, temperature, and a light-scattering sensor.

The Search Is On

Hydrothermal vents begin to form beneath the sea floor, where super-heated water flows through cracks in the Earth's crust, becoming enriched with dissolved elements from the crust that the water can contain only at extreme temperatures. Click image for larger view, full caption, and image credit.

Scientists believed there were black smoker chimneys on the Galapagos Spreading Center, but none had ever been found. One key objective of this mission was to use a variety of sensors and systems to track down a black smoker. According to Haymon, some scientists thought the influence of the Galapagos hotspot on the Galapagos Spreading Center may inhibit formation of cracks required to provide deep, hot fluid pathways for black smokers, making smokers rare and hard to find. But, the team methodically searched the ocean with chemical sensors to find plumed concentrations of chemicals that would be associated with, and take the appearance of, the black smoke of the chimneys.

Discovery!

Scientists collected plume water samples, and the strong "rotten-egg" smell of hydrogen sulfide indicated they had sampled the plume near its source. Next, they lowered a camera platform, allowing the camera to hover over the sea floor and move slowly across its surface. On the ship above, scientists watched as the camera sent up images—first wisps of smoke that became thicker. Suddenly, in the forward-looking video camera, scientists saw the black smoker chimney! They had sleuthed their way to the first black smoker ever found on the Galapagos Spreading Center.

A Lasting Impression

Scientists on the 2002 mission to Rosebud took specimens of giant chemosynthetic clams that measured nine inches across. Later, the specimens would be named Calyptogena magnifica, and one of them would accompany me to NOAA exhibits. After I told my story about the giant clams, I'd have one more message for those gathered. "It's OK if you want to touch the clam shell," I'd say. "Then, when you get home, you can tell your friends you touched 'alien' life today, and you'd be telling the truth!"

That brought out a number of smiles, followed by a few kids who came up for a clam touch. They opened the gates for the rest, young and old. It seems a lot of people want to have close encounters with alien life, and to live to talk about it. Maybe when they tell their stories to friends, they'll include something about science and the wonders and great mysteries still hidden by the ocean. And, maybe they'll remember that one mission of NOAA is to explore that great unknown ocean, for the purpose of discovery and the advancement of knowledge.

Contributed by Fred Gorell, NOAA's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research