NOAA Enhances Its Ability to Provide Tsunami Warnings

NOAA has the primary responsibility for providing tsunami warnings to the nation and a leadership role in tsunami observations and research. NOAA, along with the U.S. Geological Survey and other state and federal partners, has created a comprehensive tsunami warning system for the United States.

As we learned from the major tsunami event of December 2004 that affected so many countries including Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia, although large tsunamis are rare, they can have a devastating impact on the lives and livelihoods of those affected.

NOAA has been at the forefront of tsunami research since the mid-1940s. Following the devastating December 2004 tsunami, NOAA stepped up its ability to provide reliable warning systems that can help to mitigate damage from these potentially deadly waves. This article looks at the recent evolution and current capabilities of NOAA's tsunami program.

A Warning System Buildup

This image shows the 1946 tsunami inundating Hilo, Hawaii. Click image for larger view and complete caption.

NOAA has a long history of tsunami research and warning operations.

NOAA first began exploring the development of a tsunami warning system

in 1946, when a tsunami originating in the Aleutian Islands struck Hawaii,

killing more than 150 people. A few years later, in 1949, NOAA's National

Weather Service established the Richard H. Hagemeyer Pacific Tsunami Warning

Center in Ewa Beach, Hawaii.

Tsunami damage at Kodiak, Alaska, following the 1964 Good Friday earthquake. Click image for larger view.

The West Coast/Alaska Tsunami Warning Center, in Palmer, Alaska, was established by NOAA's National Weather Service in 1967 as a direct result of the great Alaska earthquake that occurred on March 27, 1964. Of the 132 deaths, 122 were attributed to the Pacific-wide tsunami generated by the magnitude 9.2 earthquake.

Today's Expanding Capabilities

The December 2004 Boxing Day tsunami in Indonesia is another historic event that accelerated NOAA's efforts to increase its tsunami research program and operational capabilities. Since December 2004, NOAA has developed tsunami models for at-risk communities, staffed its warning centers around the clock, expanded the warning coverage area, deployed additional Deep-ocean Assessment and Report of Tsunamis (DART) buoy stations, installed sea level gauges, and expanded community education through a program called TsunamiReady.

Tsunami Models

NOAA Research has developed new tsunami impact forecast models for major U.S. coastal communities at high risk for tsunamis. The models are used to create inundation (flood) and evacuation maps for emergency managers in the event of a tsunami and to help NOAA's National Weather Service warning centers forecast tsunamis.

24-7

Staff are on-site round-the-clock at the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center in Hawaii. Click image for larger view.

NOAA National Weather Service's two tsunami warning centers are now staffed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, in Ewa Beach, Hawaii, and the West Coast/Alaska Tsunami Warning Center, in Palmer, Alaska, hired 15 employees to staff the centers day and night. Warning center operations previously depended on staff being available by pager and able to reach the facility within minutes.

The centers are responsible for issuing tsunami advisories, watches, warnings, and information messages to emergency management officials and the public. Warnings are broadcast through NOAA Weather Radio-All Hazards, NOAA Weather Wire, the Emergency Alert System, and the Emergency Managers Weather Information Network.

Expanding the Network

Information on tsunami threats is now provided beyond the Pacific Ocean. With an enhanced communications network, NOAA National Weather Service's warning centers are now capable of alerting the U.S. Atlantic Coast, Gulf of Mexico, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Eastern Canada. Before December 2004, no warning system existed for these areas.

Today, the West Coast/Alaska Tsunami Warning Center is responsible for the U.S. Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, Alaska, U.S. West Coast, and the British Columbia and Atlantic coasts in Canada. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center provides tsunami warnings to most countries in the Pacific Basin, as well as to Hawaii and all other U.S. interests in the Pacific outside of Alaska and the U.S. West Coast. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center's area of responsibility also includes Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

In addition, the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, in partnership with the Japan Meteorological Agency, is providing tsunami advisory and watch alerts to 20 Indian Ocean countries on an interim basis, until regional warning centers can be established in these areas.

DART Buoys, Sea-level Stations, and Archives Improved

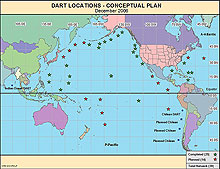

This map shows the location of DART buoys as of 2006. Click image for larger view.

NOAA's DART network was expanded from six to 19 DART buoy stations and now also includes the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea. The original six buoys were all located in the Pacific.

Developed by NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and operated by NOAA's National Data Buoy Center, the stations provide real-time tsunami detection as waves travel across the open ocean. In early April 2005, NOAA launched the first DART buoys in the Atlantic. The current network consists of 14 DART stations in the Pacific and five in the Atlantic/Caribbean. All newly installed stations are the more robust DART II buoy with advanced two-way satellite communication.

All newly installed stations are the more robust DART II buoys with advanced two-way satellite communication that allow warning center staff to "interrogate" the station for information. Click image for larger view.

In addition, in 2005-2006, NOAA's Ocean Service installed 15 new sea-level stations and upgraded 33 others. These automated stations are located closer to shore than the DART stations. The sea-level stations record water level in one-minute intervals, then transmit that data via satellite to the tsunami warning centers.

Finally, the quality and accuracy of the long-term archive of tsunami events has been improved. NOAA's Satellite and Information Service global database includes information on nearly 2,000 tsunamis from 2000 B.C. to the present. This database is used to identify regions at risk, validate tsunami models, help position detection sensors, and prepare for future events. NOAA has quality-assured/quality-controlled data for 75 percent of the tsunamis that have impacted U.S. coasts and 50 percent of the most deadly global tsunamis. This archiving work entails identifying and documenting tsunami sources; the date, time, and magnitude of earthquakes; maximum water heights; deaths; and damage.

Are You TsunamiReady?

NOAA and partners work to increase public education and outreach, so that communities know what to do in the event of a tsunami.

Through its voluntary TsunamiReady program, NOAA's National Weather Service works with communities to prepare evacuation plans, enhance communications, and heighten awareness of tsunamis for both residents and visitors. NOAA's National Weather Service has recognized over 30 communities as TsunamiReady, including:

- May 2005: Tillamook County, Oregon, became the first TsunamiReady county in the continental United States.

- July 2005: Indian Harbor Beach, Florida, was recognized as the first East Coast TsunamiReady community.

- December 2005: All counties in Hawaii were recognized as TsunamiReady, making Hawaii the first TsunamiReady state.

- January 2006: Norfolk, Virginia, was the first major city on the East Coast to become TsunamiReady.

It All Adds Up

An effective tsunami warning system must include hazard detection, risk assessment, warning dissemination, and a public that understands what to do when a warning is sounded. Since December 2004, NOAA has led the U.S. effort to build a comprehensive tsunami warning system that includes all of these elements. The result is a nation better equipped to detect a tsunami and alert communities of the impending danger.

Works Consulted

NOAA Magazine. (2004). NOAA reacts quickly to Indonesian tsunami. Retrieved October 30, 2006, from: http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2004/s2357.htm.

NOAA. (2006). NOAA's National Geophysical Data Center Web site. Retrieved October 30, 2006, from http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov.