Wave Power: Looking to the Ocean for Electricity in Oregon

NOAA's Sea Grant program is a nationwide network of 30 university-based programs that work with coastal communities. This successful federal-university partnership program promotes better understanding, conservation, and use of America’s coastal resources through research and outreach.

With the U.S. breaking record highs for power use, many researchers and utilities are looking to alternative power sources to add to our nation’s electrical grid. Some are eyeing the ocean as a new, potent source of renewable energy.

Harnessing the power of ocean waves could provide the renewable energy of the future.

There are numerous potential ways to tap the ocean for energy, from tides, currents, salinity, and even harnessing its thermal features. However, wave energy may be the most promising source of ocean energy for the U.S. coastline, particularly in the Pacific Northwest.

NOAA, through the Sea Grant program, is supporting Oregon State University in exploring this potentially powerful source of energy.

The Energy of the Future…Today

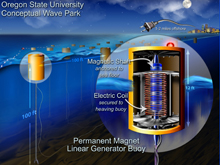

While wave energy may sound futuristic, pilot projects are in the water in Europe, Australia, Asia, and Hawaii. Ocean Power Technologies, Inc., of New Jersey, recently announced it is pursuing permitting for the first U.S. commercial site in Oregon. Oregon State University is working to develop a national wave research park to study wave technology, as well as numerous other existing and potential wave technologies.

For the past eight years, researchers at Oregon State University have been developing prototypes of new wave energy technology. In the search for research funds, they turned to Oregon Sea Grant. Click image for larger view.

“It’s real,” Roger Bedard, ocean energy leader for the nonprofit Electric Power Research Institute, Inc. (EPRI), says of wave power. “Given proper siting, it probably will turn out, in my opinion, to be one of the more environmentally benign electricity generation [technologies] known to human kind.”

Potential environmental impacts and user conflicts are the key concerns for NOAA partner programs in Oregon. For the past several years, these programs have helped bring together researchers, fishermen, state and federal agencies, utilities, and numerous other stakeholders to identify and address any areas of concern with wave energy and map the potential regulatory process.

Being Dense Is a Good Thing

Wave power devices extract energy directly from surface waves or from pressure fluctuations below the surface, and are typically located two to three miles (three to five kilometers) offshore. Waves off the coasts of Oregon, California, Washington, Alaska, and Hawaii have been identified as good sites for the development of wave energy.

One only needs to watch the rhythmic rolling of ocean waves to see their potential as an energy source. The density of ocean water—about 1,000 times that of wind—also is significant to its potential for generating electricity, as is the ability to predict waves hours before they hit shore using existing ocean buoys, such as the one shown here.

“Ocean wave electricity generation is about where wind generation was 15 to 20 years ago, but it’s catching up faster then expected, and is much closer then we initially thought,” notes Bob Malouf, director of Oregon Sea Grant.

As wave technology improves, it is believed that less ideal wave environments might become more accessible as an energy source, and that wave energy facilities could be sited further offshore.

Ultimately, Bedard believes wave power could provide about 10 percent of the country’s electricity needs. While this may not sound like much, Bedard argues, “If we had 10 percent of our energy from waves, 10 percent from solar, 10 percent from wind, 10 percent from hydropower—that would be great. As natural gas becomes more and more expensive, we will see renewable resources like these come more into play as economically viable.”

Researching the Way

For the past eight years, researchers at Oregon State University have been developing prototypes of new wave energy technology, and have pursued the creation of a national wave research and development park.

Researchers at Oregon State University are working to develop a national wave research park to study wave technology, as well as numerous other existing and potential wave technologies. Click image for larger view.

In the search for research funds, they turned to Oregon Sea Grant.

“When their first proposal came to us, we weren’t interested. I frankly thought they were naive,” Malouf recalls. Sea Grant’s citizen advisory board, however, overwhelmingly supported the project.

Sea Grant’s criteria for the funding were that the researchers participate in their Port Liaison Project to develop a collaborative partnership with fishermen and crabbers who ply Oregon's coastal waters. The fishermen provide ocean technical expertise and input on wave-park siting issues.

“We are not advocating the development of this,” Malouf says. “Our role is to be a liaison between the fishing community and the various groups. We are advocating honest and open public discussion about” the potential wave energy projects.

No Take Zone

The primary concern of most fishermen, says Al Pazar, chair of the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission and the owner/operator of two fishing vessels, is that the area around any wave park would be off limits to all uses, including fishing.

The Dungeness crab, Cancer magister, is an important commercial species. They range from the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea to Santa Barbara, California. Their preferred habitat is sandy bottom and eelgrass beds, where they are often buried during daylight hours.

In 2004, EPRI did a feasibility study funded by Bonneville Power and Central Lincoln Utility District to identify sites in Oregon that would be good for either a wave research park or commercial wave energy facility. The site that rose to the top happens to be a prime Dungeness crab fishery.

“To the credit of the researchers and state folks, they’ve included the public every step along the way,” says Pazar. While not all fishermen support the research and commercial projects, he says most are “not throwing up many walls. We’re working with them to try to minimize the impacts as much as possible.”

State Interest

With Oregon State University blazing the research trail, state agencies began to pay attention to wave energy, says Greg McMurray, marine affairs coordinator for the Oregon Ocean and Coastal Management Program.

Wave energy development, says Justin Klure, senior policy analyst with the Oregon Department of Energy, was a natural fit with the governor’s Action Plan for Energy that establishes the goal that by 2025, renewable resources will meet 25 percent of Oregon’s energy needs.

Oregon’s Department of Energy organized state and federal agencies, local officials, utilities, fishermen, and other stakeholders to look at wave energy and how the state might address any problems when siting a wave energy project. The group became known as "People of Oregon for Wave Energy Resources," or POWER.

Answering the Unknown

While pilot projects around the world have reported little to no environmental impacts, the greatest unknown about wave energy is how a commercial facility will affect the ocean environment.

Researchers from Oregon State University are exploring new and innovative was to harness wave energy. Click image for larger view.

Potential environmental impacts include withdrawal of wave energy on the ecology; interactions with marine life, such as migrating gray whales; any atmospheric and oceanic emissions; noise; bottom impacts from anchors; and visual appearances. Environmental impacts from cable landings are a concern, as are electrical and magnetic energy imparted into sea water. A wave energy facility also could pose a threat to navigation.

Bedard notes that since wave energy facilities are located several miles off shore and have a relatively low profile, facilities will probably have little visual impact. Wave energy produces no air emissions, and would have little to no ocean emissions, depending on the technology and anti-fouling measures used.

Careful site selection, Bedard says, is the key to keeping environmental impacts of wave power systems to a minimum. For instance, sites can be chosen outside whale migratory routes or to avoid areas where sediment flow patterns on the ocean floor would be significantly altered.

Regulatory Routes

The POWER group is also working to map local, state, and federal permitting and regulatory issues that will be faced. The group is providing information to the state’s Ocean Policy Advisory Council, which recommends future state policies on a wide variety of ocean management issues. By statute, the director of Oregon Sea Grant is a member of the Ocean Policy Advisory Council, and the group is staffed by the Oregon Ocean and Coastal Management Program.

John Baylouny, senior vice president of engineering for Ocean Power Technologies, says they have filed a preliminary permit application with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). This application is requiring the company to “sit down with FERC and discuss which agencies might be interested parties, talk to them, and find out what their needs might be, so that we can address their issues in our application for license.”

McMurray notes that the coastal program will be able to apply federal consistency—a provision of the Coastal Zone Management Act requiring that federal activities be consistent with the policies of state programs—to Ocean Power Technologies’ permit application.

George Hagerman, senior research associate at Virginia Tech’s Advanced Research Institute in Arlington, Virginia, notes that the Minerals Management Service is currently developing its regulatory policies for alternative energy facilities located outside state waters. “The rule making for those regulations is happening now,” Hagerman says, “and will directly affect coastal resource managers."

Going Commercial

Baylouny says that part of the reason his company selected Oregon as the location for its first U.S. commercial wave energy facility is the work the state has already done to engage the community. The ideal wave resources, existing grid connections, and the state’s package of incentives were other inducements.

“Oregon has been very progressive in their efforts to develop a new industry in their state,” Baylouny says. “It’s clear they want to be the leader in wave power in the U.S.”

“Whatever we might think of it personally, our job is to make sure the dialogue continues,” Malouf says. “We will continue to help involve the community. When it comes time to put test materials out there, we want it to be a fisherman’s vessel that does it. We want that level of cooperation with the community, and Sea Grant can help do that.”

Malouf adds, “I’d like to see Sea Grant and NOAA act like a network or one program, so that when wave energy does happen in other states, we can share some of the lessons we have learned. We can help.”

With efforts like these underway, it is hoped that the ocean can be tapped as a new, potent source of renewable energy for this country.