NOAA Reveals History in...The Great Ocean Museum

Established in 2001, NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration sponsors exploration and science-based projects that locate, identify, and survey submerged cultural resources to better understand our maritime heritage. Maritime heritage projects with the Office of Ocean Exploration’s involvement have spanned across the globe, covering thousands of years of history, and involved many NOAA programs.

- Introduction

- Sanctuaries Protect Shipwrecks

- Other Underwater Treasures

- Naval History

- Ships in Alaskan Waters

- The Search Continues

The science team and ship’s crew recover IFE’s Hercules ROV and prepare to place it on the fantail of the Research Vessel Knorr while a National Geographic camera team films the operation from a small boat. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The Hercules, a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) descended into the Black Sea’s dark waters. The ROV dropped into the anoxic layer—water with no oxygen to support life. This was the dead zone, free of wood-boring worms that eat away at wooden ships. On the seafloor was the wreck of a 1,500-year-old merchant ship, with a defiant mast rising 35 feet high.

NOAA Corps’ Lieutenant Jeremy Weirich examined the wreck from a research vessel on the water’s surface. “We first saw the ship’s wooden stern post, a large piece of crafted wood that stood up proud off the bottom,” he said. The top of the mast revealed more clues about the ship and those who sailed it. “Fastened near the top there’s a knotted binding that could be a piece of leather. Someone tied that knot,” Weirich said.

The Black Sea mission taught valuable lessons on how to locate and protect ancient artifacts and ships of antiquity. The mission was one of several partnerships between NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Bob Ballard, discoverer of the Titanic shipwreck.

Ballard looks at the ocean as a “great museum,” a preserver of history. “There's probably more history now preserved underwater than in all the museums of the world combined,” he says.

One NOAA mission, often shared by NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration, NOAA's Undersea Research Program, and NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program, is to discover these lost shipwreck “museums,” and other submerged cultural and historic resources.

Sanctuaries Protect Historic Shipwrecks

One piece of history uncovered from ocean depths was the USS Monitor. The ironclad USS Monitor, revolutionary in her design, was rushed into service in 1862 to face the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimack).

Navy divers celebrate as the turret of the USS Monitor breaks the surface August 5, 2002, off the coast of Hatteras, North Carolina. Image courtesy of AP Pool/Steve Early.

Monitor’s short career ended in a gale off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Her remains were discovered by a team of scientists in 1973. The NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration co-sponsored efforts in 2001 and 2002 with other NOAA partners, the U.S. Navy, and the Mariners’ Museum to recover and conserve the Monitor’s steam engine, a significant portion of its hull, and the ship’s 140-year-old gun turret.

Today, a National Marine Sanctuary protects the waters where the Monitor sank.

Sunk in 1865, the wooden passenger steamer Pewabic rests in 160 feet of water in NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. This photomosaic of the wreck was created from high-resolution imagery collected during a two-week project in the sanctuary with funding from the Office of Ocean Exploration. Click image for larger view and image credit.

While the Monitor represented the first sanctuary protecting a cultural resource, the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and Underwater Preserve was established in 2000 to protect a nationally significant collection of shipwrecks spanning more than a century of Great Lakes maritime history and located entirely in Michigan State waters. Office of Ocean Exploration-funded research in Thunder Bay has discovered new wrecks and supported archaeological exploration of these sites.

Other Underwater Treasures

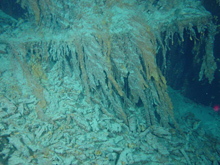

Detached rusticles below port side anchor of the Titanic indicating that the rusticles pass through a cycle of growth, maturation, and then fall away. This particular “crop” of rusticles probably was in a five to ten-year cycle. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Shipwrecks are not the only craft to have been claimed by the Great Lakes. In 2004, an Office of Ocean Exploration-funded remote sensing survey of Lake Michigan searched for historic World War II aircraft that had been lost during training exercises in the 1940s. “The group of aircraft is the only collection of historic, World War II, Navy aircraft preserved in cold, fresh water,” said Wendy Coble, aviation specialist in the Underwater Archaeology Branch of the Naval Historical Center. “This study has provided information not obtainable anywhere else.”

A view of the bow of the Titanic from a camera mounted on the outside of the Mir I submersible. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Another unique ocean treasure lies in the North Atlantic Ocean. On a mission in 2004, Bob Ballard returned to the wreck of RMS Titanic, nearly two decades after he discovered the site in 1985. Titanic lay on the ocean floor more than two miles below NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown. Scientist-explorers on the Brown studied colonies of bacteria that consumed iron from the ship's steel, forming rusticles, so named because they looked very much like rusty icicles, giving the appearance of a ship melting away.

Scientists also inspected damage from previous submersible landings to help determine how much of the ship's deterioration was caused by nature, and how much by man. Today, NOAA is charged with protecting the wreck site under the Guidelines for Research, Exploration and Salvage of RMS Titanic that NOAA prepared. The Office of Ocean Exploration is the program lead for all Titanic information.

Naval History

The wreck of a Japanese midget-submarine sunk by an American destroyer at the entrance to Pearl Harbor just prior to the air attack on December 7, 1941, is imaged using a manned submersible operated by NOAA’s Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory at the University of Hawaii. Figure-eight-shaped antisubmarine net cutters are visible on the sub’s bow, while the lights from a second sub can be seen as it approaches the stern. Image courtesy of Terry Kerby, HURL, University of Hawaii.

Not all discoveries of maritime heritage sites result from specific maritime archaeological missions. NOAA’s Undersea Research Program and Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory know this well. Operational test and training dives on their manned submersibles Pisces IV and Pisces V in August 2002 yielded the discovery of a 78-foot Japanese midget submarine sunk before the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, solving a mystery more than 60 years old.

Before the air attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor began on the morning of December 7, 1941, the crew of the U.S. destroyer Ward reported that the ship had fired on and hit a surfaced submarine as it approached the harbor entrance. Ward’s report was largely discounted at the time, and without evidence, the crew’s claim remained suspect for more than six decades.

All suspicion ended when the National Undersea Research Program at the University of Hawaii discovered the submarine during a training dive in 2002. The four-inch hole in its conning tower was evidence that crewmembers of the U.S. destroyer Ward were right when they claimed to have fired the nation's first shot of World War II, more than a hour before the air attack on Pearl Harbor. The midget submarine is still armed with two intact torpedoes, and with the hatch closed, the vessel is likely the sea grave of the two-man Japanese crew.

In February 2004, the Government of Japan agreed that the midget submarine was now the property of the U.S. government. In a partnership with other federal agencies, NOAA is playing a key role in the protection and management of the midget sub under the provisions of U.S. policy on sunken vessels and historic preservation laws and policies.

Ships in Alaskan Waters

This shipwreck was positively identified when archaeologists discovered the hub of the ship's wheel bearing the Russian name for Kodiak, Kad'yak (in Cyrillic - ![]() ). Click image for larger view and image credit.

). Click image for larger view and image credit.

Alaska contains more than half of today’s U.S. coastline. An expedition led by Brad Stevens of the NOAA Kodiak Fisheries Research Center in July 2003 discovered the remains of what was believed to be the Russian-American Company’s bark Kad’yak, which sank in Icon Bay off Spruce Island, Alaska in 1860.

In 2004, Frank Cantelas of East Carolina University co-led a dive team on an Office of Ocean Exploration and National Science Foundation-sponsored mission to verify the wreck was that of Kad’yak.

Today, Cantelas is the Maritime Archaeology Program Coordinator in NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration. “Any question about the ship’s identity was answered when we recovered a brass object we believe is the hub of the ship’s wheel,” said Cantelas. “When we turned the hub over, it was as if the vessel spoke to us when we saw the ship’s name clearly inscribed in Russian.”

The Hassler

The icy waters of Alaska hold many other shipwrecks. One Alaskan shipwreck discovery takes on special meaning as NOAA celebrates the 200th anniversary of its oldest ancestor agency. This is the late-19th century U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey vessel named for that agency's first superintendent, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler. The Hassler accomplished important hydrographic mapping in Alaska before being sold for passenger service.

The Klondike gold rush steamer Clara Nevada was originally built as the hydrographic survey vessel Hassler in 1872. Named after the first superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler, she steamed through the Straits of Magellan with famed naturalist Jean Louis Agassiz and spent many years hard at work in Alaska. Photo courtesy of the Alaska Historical Society.

Renamed Clara Nevada, the ship became a Klondike gold rush steamer. “It's not clear how the 150-foot vessel was lost," said Hans Van Tilburg, maritime archaeologist and maritime heritage program coordinator for the NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Program’s Pacific Islands Region. "The ship was heading south down Lynn Canal from Skagway in 1898, when witnesses on shore reported seeing a bright orange fireball, then a ship burning near Eldred Rock."

All on board the vessel perished on what was the return leg of the first voyage after the vessel entered commercial service. The ship's demise provided sufficient evidence of the need for construction of the Eldred Rock Lighthouse, currently one of the oldest remaining lighthouses in the state of Alaska.

The Search Continues

Today, NOAA includes in its mission the discovery, initial survey, and protection of shipwrecks and other submerged historic cultural resources that have been hidden in the ocean’s great museum. NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and National Marine Protected Areas Center work cooperatively with NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program, housed within the NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Program. With its partners, maritime archaeology projects sponsored by NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration have discovered or surveyed the shipwrecks in this story and many others. These and other missions will fill in some of the blank pages of world and U.S history.

Thousands of other sites rich with human history lay undiscovered on the seafloor. Through explorations of discovery, NOAA hopes to bring these treasures to light. With a combination of exploration and innovative technology, more and more of the ocean’s great museum will open to the public.

Contributed by Kelley Elliott and Fred Gorell, NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research