Disaster Response: NOAA Ships, Planes, and Officers Offer Valuable Capabilities

Though not officially a part of the agency’s mission, disaster response has put NOAA under the national spotlight during the past 20 years. NOAA ships and aircraft, under the management and leadership of NOAA Corps officers, have unique capabilities that enable them to play an important role in search, recovery, and mitigation efforts following a disaster.

- Introduction

- The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

- Gulf War Impacts

- TWA Flight 800 Airplane Crash

- JFK, Jr. Airplane Crash

- Egypt Air Flight 990 Plane Crash

- September 11, 2001

- Hurricane Katrina

- Prepared for Rapid Response

NOAA ships, aircraft, and commissioned officers—which all fall under NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations—work year-round to support the agency’s environmental and scientific missions. NOAA's fleet of 19 ships provides hydrographic survey, oceanographic and atmospheric research, and fisheries research vessels to support NOAA's mission. NOAA's fleet of 11 aircraft operates throughout the United States and around the world—over open oceans, mountains, coastal wetlands, and Arctic pack ice. These versatile ships and aircraft provide scientists with the platforms necessary to acquire the environmental and geographic data essential to their research.

NOAA’s smallest ship, Rude, and light Citation II jet have played key roles in national disaster response efforts.

Over the past 20 years, NOAA vessels and aircraft have increasingly been called on to apply their unique capabilities in response to a range of disasters, from the Gulf War to the 9/11 attacks.

This article reviews some of the many incidents in the past 20 years where either NOAA ships or aircraft, managed by NOAA Corps officers, were called on to respond to a disaster.

The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: March 24, 1989

The supertanker Exxon Valdez ran aground and spilled about 10.8 million gallons (38,800 tons) of crude oil into Alaska's Prince William Sound. The Valdez spill became the largest marine oil spill in North America. Oil ultimately coated about 1,200 miles (1,900 kilometers) of coastline, up to 470 miles (750 kilometers) away from the site of the accident. No human lives were lost, but 20 communities and a rich natural environment were severely affected.

NOAA Response

The NOAA ship Fairweather supported damage assessment and biological sampling operations after the grounding of the Exxon Valdez.

The NOAA ship Fairweather, a 231-foot (70-meter) hydrographic survey ship, was inactive in Seattle, Washington, at the time of the grounding. After this massive oil spill, the ship was quickly retrofitted with hydrographic survey launches to conduct shoreline surveys, and oceanographic instrumentation for biological and sediment toxicity surveys. This enabled the ship to support damage assessment and biological sampling operations at the site of the grounding. Fairweather, joined by the NOAA ship Davidson, conducted this multidisciplinary mission for several months after the grounding. Based on the work performed by scientists aboard Fairweather, numerous scientific papers were published that examined the effects of the oil spill on the marine ecosystem in Prince William Sound.

Gulf War Environmental Impacts: January, 1991

In January of 1991, more than 740 Kuwaiti oil wells were destroyed as part of the Gulf War conflict. The destruction of these wells released six to eight million barrels of crude oil into the Persian Gulf, resulting in catastrophic environmental damage in the Gulf region.

NOAA Response

Crew members and scientists aboard the Mt. Mitchell during the 1992 Persian Gulf cruise.

Between February and June 1992, the NOAA ship Mt. Mitchell conducted a 100-day, multi-disciplinary oceanographic research investigation in the Persian Gulf, involving more than 140 marine scientists from 15 nations. The expedition was pulled together in about three months—with Mt. Mitchell being refitted with hydrographic survey launches and oceanographic sampling instrumentation for the mission; more than 140 scientists identified; research plans agreed to; country clearances obtained; and food, dockage, and fuel resources made available in the region.

The mission was a great success — measured not only by the wealth of scientific data collected, but also in the strides made in local, regional, and international environmental awareness and cooperation in the Gulf. Through the work of the ship, physical oceanography data provided information needed to accurately model future oil spills in the Arabian Gulf.

The ship's multi-disciplinary investigation identified biological, chemical, and physical impacts from the oil spill along the most heavily affected shoreline—Ras al Tanaqib to Ras Abu Ali, Saudi Arabia. Ship researchers investigated the effects of oil on commercial fisheries resources and the supporting ecosystem and on the coral reefs of the region. Scientists from NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service conducted critical fish/shellfish oil contamination assessments. Scientists set up a laboratory on board the vessel to do real-time, high-quality analyses of biological samples to assess exposure to oil. An additional leg was added to the project to gather more physical and biological oceanographic information about the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman and to train Omai students from Sultan Qaboos University.

TWA Flight 800 Airplane Crash: July 17, 1996

At approximately 8:45 p.m., shortly after takeoff from Kennedy International Airport, TWA flight 800, a Boeing 747, crashed into the Atlantic Ocean eight miles (13 kilometers) off the coast of Long Island, New York. The airplane was on a regularly scheduled flight to Paris, France. The initial reports were that witnesses saw an explosion and then debris descending to the ocean. On board the airplane were 212 passengers and 18 crewmembers. The airplane was destroyed and there were no survivors.

NOAA Response

Crewmembers aboard Rude assist with debris recovery following the TWA Flight 800 disaster.

At the request of the U.S. Coast Guard, the NOAA ship Rude transited all night from its hydrographic survey working grounds in Rhode Island Sound and arrived at the scene less than 12 hours after the crash. After assisting in the search for survivors and recovery of floating debris, Rude conducted a side scan sonar survey of the crash area.

Within days, Rude had mapped the full extent of the underwater wreckage. This survey was invaluable to Navy divers whose job it was to recover the victims and ultimately the airplane wreckage.

JFK, Jr. Airplane Crash: July 16, 1999

John F. Kennedy, Jr., his wife Carolyn Bessette, and his sister-in-law Lauren Bessette were killed when their Piper aircraft crashed in the Atlantic Ocean near Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, on July 16, 1999.

NOAA Response

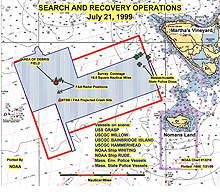

This NOAA chart shows search and recovery operations that took place following the JFK, Jr. plane crash. Click image for larger view.

At the request of the U.S. Coast Guard, the NOAA ship Rude was called from its hydrographic survey grounds in Long Island, New York, to assist in search operations for the missing plane. Little was known about the location of the plane crash, so Rude began an expansive side scan sonar survey in the waters that approached the Martha’s Vineyard airport.

Two days later, the NOAA ship Whiting arrived from its working grounds in Delaware Bay to assist in the search.

After three days of surveying, Rude discovered a suspicious object on the ocean bottom. The crew dropped a temporary buoy on the target. Navy divers soon thereafter identified the target as the missing plane.

Egypt Air Flight 990 Plane Crash: October 31, 1999

Egypt Air Flight 990 was a Los Angeles-New York-Cairo flight operated by EgyptAir. At around 1:50 a.m. on October 31, 1999, Flight 990 dove into the Atlantic Ocean, about 40 miles (65 kilometers) south of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. Killed in the crash were 217 passengers and crew.

NOAA Response

NOAA united to provide comprehensive services following the Egypt Air 990 crash. Search efforts were led by NOAA Corps Commander Steve Barnum.

The NOAA ship Whiting immediately steamed to the crash site from its working grounds in Delaware Bay. Whiting began a hydrographic survey of the crash site. On its first survey line, Whiting found the airliner’s major debris field. Whiting created a map, or mosaic, that enabled the Navy salvage ship Grapple to anchor safely in the debris field without disturbing the wreckage.

World Trade Center and Pentagon Terrorist Attacks: September 11, 2001

On September 11, 2001, two hijacked passenger planes crashed into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, one plane into each tower. Both towers collapsed within two hours. Another passenger plane crashed into the Pentagon outside Washington, DC. More than 3,000 people were killed in the 9/11 attacks.

NOAA Response

NOAA aircraft flew several missions over the World Trade Center and Pentagon after the events of September 11th, to aid in the recovery efforts.

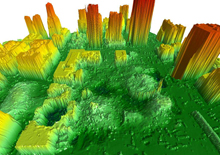

The NOAA Citation jet mapped Ground Zero using aerial photography and LIDAR technology, which was used to generate this image. Click image for larger view.

NOAA's Citation jet mapped the devastation in New York City using aerial photography and Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) technology. The data collected by the LIDAR equipment helped to produce three-dimensional images of the site where crews continued their recovery and cleanup efforts.

These images helped to identify the height of the rubble so the appropriate cranes could be used to remove it. The data collected from the fly-overs provided building and utility engineers the information needed to locate original foundation support structures, elevator shafts, and basement storage areas. This information allowed the crews to pinpoint their digging and recovery efforts.

Hurricane Katrina: August 23-31, 2005

Hurricane Katrina, which struck the U.S. Gulf Coast in August, 2005, was the costliest and one of the deadliest hurricanes in the history of the United States. It was the sixth-strongest Atlantic hurricane ever recorded and the third-strongest landfalling U.S. hurricane ever recorded. Most notable in media coverage were the catastrophic effects on the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, and in coastal Mississippi.

Katrina's sheer size devastated the Gulf Coast over 100 miles (160 kilometers) away from the hurricane’s center. Katrina is estimated to be responsible for $81.2 billion in damages, making it the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

NOAA Response

This view of Grand Isle, Louisiana, was taken by a NOAA Citation jet two days after Hurricane Katrina ripped across the Gulf Coast. Click image for larger view.

NOAA’s WP-3D and Gulfstream-IV hurricane aircraft provided meteorological data from the heart and periphery of the storm, enabling the National Hurricane Center to make accurate track and landfall forecasts. The day after Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the U.S. Gulf Coast, NOAA began aerial photography flights over the affected areas. For nine days, the NOAA Cessna Citation aircraft flew two to three missions each day, only stopping to refuel. Nearly 7,000 aerial images were produced from these missions and made available to the public through the Web. An interface with Google enabled emergency workers, public officials, and residents to view affected areas online to see if bridges, roads, and homes were still standing.

The NOAA ship Nancy Foster, a coastal research ship, was quickly outfitted after Hurricane Katrina to conduct seafloor surveys. Under the command of an experienced hydrographer, Nancy Foster surveyed the approaches to Mobile, Alabama, for obstructions, helping to reopen the port to navigation. This ship was then re-equipped to conduct environmental damage surveys.

In addition, the NOAA ship Thomas Jefferson was diverted from its working grounds to conduct hydrographic surveys around the entrances to Pascagoula and Gulfport, Mississippi, helping to quickly reopen the ports to maritime commerce. The crew also replaced lost or damaged tide gauges.

NOAA Ships, Aircraft, and NOAA Corps: Prepared for Rapid Response

While each of these disasters required unique NOAA capabilities, all responses possessed one common component: NOAA ships and aircraft, under the command of NOAA Corps officers, responded rapidly and effectively when called upon to assist. For example, responses to the crashes of TWA Flight 800, Egypt Air 990, and JFK, Jr.’s plane yielded critical results to emergency managers, each within a matter of a few days. The TWA Flight 800 and Egypt Air 990 underwater crash sites were surveyed within 48 hours of the respective crashes. The JFK, Jr. lost airplane—a needle-in-the-haystack search—was located four days after the crash.

Over the past 10 years, NOAA’s disaster response has evolved to efficiently incorporate all aspects of the agency. While the 1996 NOAA response to the TWA Flight 800 disaster was effective, it was somewhat piecemeal as individual NOAA programs independently presented their capabilities to the Coast Guard and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

However, by 1999, when NOAA responded to the Egypt Air 990 crash, the agency came together, providing a survey ship, marine forecasts, weather buoy observations, current predictions, and analysis and fisheries expertise. NOAA Corps Commander Steve Barnum stood side-by-side with NTSB Chairman James Hall during most of the public and private briefings on the Egypt Air crash.

Today, federal agencies such as the Coast Guard and NTSB are much more aware of NOAA’s disaster response capabilities. NOAA ships, aircraft, and the NOAA Corps are important assets in this comprehensive NOAA response.