What is Coral Bleaching?

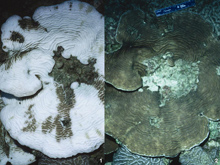

An Agaricia coral colony shown: 1) bleached, and 2) almost fully recovered, from a bleaching event. Click image for larger view and image credit.

As atmospheric temperatures have increased in recent decades, so has the temperature of the ocean’s surface waters. Corals are stressed when water temperatures are as little as one degree Celsius warmer for a week or more, especially when there are no winds to mix surface waters and provide relief from the strong sun and ultraviolet (UV) rays.

Corals stressed by temperature and UV rays may expel the symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae (Zo-zan-THELL-lee) that live in their cells. These microscopic, plant-like organisms live in coral tissue and give corals most of their color. This mutually beneficial relationship between two organisms is called symbiosis. Zooxanthellae use carbon dioxide and sunlight to produce food the corals need. Corals release carbon dioxide and nutrients the zooxanthellae need.

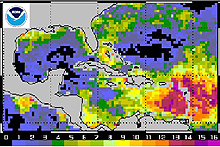

The Caribbean experienced widespread coral bleaching during the summer and fall of 2005. This NOAA Coral Reef Watch composite shows maximum Degree Heating Weeks thermal stress accumulations. View it as an animation. Image courtesy of NOAA Coral Reef Watch.

When corals expel these symbiotic algae, coral tissues become clear, revealing the corals’ white skeletons. This condition is known as “coral bleaching.” While corals have the capacity to recover from short bleaching events, severe or continued stress diminishes their ability to recover and increases their vulnerability to other stressors such as disease. If bleaching is severe or prolonged, coral colonies may die. The composition of species on the reef may also change after corals die, impacting a reef’s ability to provide habitat for other species.

During the 1997-1998 El Niño/Southern Oscillation event, warming of ocean temperatures resulted in massive coral bleaching throughout the western Pacific and Indian Oceans. Approximately 16 percent of the world’s coral reefs were effectively destroyed. This was the largest single bleaching event ever recorded to date, and alerted the world to the dramatic impact that just one bleaching episode could have on the survival of reefs in many locations.

A NOAA scientist discusses the 2005 coral bleaching event in the Caribbean. Click image to download sound file and read trasncript.

In 2005, the world experienced another record-breaking bleaching event in the Caribbean. That summer, reefs throughout the Caribbean experienced the worst mass bleaching event on record in this region, with as much as 90 percent of corals bleached and 40 percent mortality (or greater) at many sites. To add to the devastation, diseases took advantage of weakened coral, especially in the U.S. Virgin Islands, causing increased mortality. Elkhorn and staghorn corals – which in 2006 became the first corals listed as ‘threatened’ by NOAA under the Endangered Species Act – bleached and succumbed to disease, as did other coral species.

Scientists predict that bleaching may become more frequent and severe as ocean temperatures continue to increase.